We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

A wall of sequence-matched, custom-veneered panels with integral TV screen in the home of an architect client.

Recently, a woodworker who’s about to start building a set of cabinets for her own kitchen asked me how I apply heat-sensitive edge banding to doors and drawer faces when working with architectural veneers. She’d done some similar work before but had problems with tear-out during trimming.

Here’s my technique, a hybrid between the system used at the first shop where I encountered this type of veneer work and some modifications based on my experience over the 30 years since that time, all of it adapted to work with the realities of my small shop.

Commercial shops that specialize in architectural veneer work have specialized equipment for applying and trimming edge banding. Such equipment runs the gamut from the simple to the higher-end. The shop where I worked three decades ago had a piece of equipment at the simple end of the spectrum: a table fitted with a spool of veneer tape and a heated roller to melt the glue. The user slid the workpiece across the table, pressing it against the heated roller to adhere the edge-banding. Depending on the dimensions of a workpiece – say, a door for a typical kitchen base cabinet – you could band it in less than a minute.

The problem with this system? There would be spots where the heat or pressure had been inadequate, resulting in the occasional patch of loose veneer. Sometimes this was due to user error; I’m not blaming any particular brand of machine. But I was always amazed at how much time we ended up spending on checking the joints and repairing them when we found loose spots or bubbles. The solution at that shop was to take a household iron and press the patch down, followed up right away by pressing down on the veneer with a block to cement the joint.

For anyone who only edge-bands occasionally, it’s just as reasonable to forgo the banding machine and go straight to the iron. Yes, it takes longer, but it’s foolproof because you check each piece as you work along its length – and the cost is closer to $20 than $350 (or the tens of thousands of dollars the commercial equipment runs.)

My process

Start by cutting your panels to dimension, allowing for the 1/16″ or so that will be added by the thickness of the veneer on all sides. I use a Forrest saw blade designed for veneered panels. If your shop is too small to cut the panels on a table saw, or if you don’t want to buy a special blade, you can cut the panels roughly to size, then trim them precisely with a router and a straight edge, using a pattern-cutting bit.

Depending on which part of your workpiece will be more visible — the top or the side — start with the less visible edge first. For instance, in the case of the wall of sequence-matched panels above, the top and bottom veneers would be hidden from view (unless you’re a mouse or a dust mite), so I applied them first, then followed with the long side edges. This way the joint at the corner between the top (or bottom) and side would be concealed by the long grain of the side banding.

Cut or break a piece of edge banding roughly to length with enough waste to allow for trimming. I usually allow an extra inch or so. If you’re working in multiples of the same length, you can just fold the veneer in accordion fashion to replicate the length, then snap the pieces off by bending them back in the other direction.

Clamp your panel in a vise, grab a palm-size block of hardwood with clean edges and turn on your iron. I usually use the “cotton” setting.

Hold the edge-banding roughly in place with one hand so that it covers the entire edge of the panel.

Hold the edge-banding in place with one hand and get ready to press with the iron, using your other hand.

Now lay the iron on, starting at one end. Hold the iron perfectly flat for several seconds. If you look at the joint up close, you may be able to see a little glue melting out. Remove the iron and immediately press the joint with your wooden block, holding it perfectly flat. Take care not to push too hard in any particular direction, as doing so could shift the position of the edge-banding until the glue has set.

Immediately after you remove the iron, run a hardwood block over the area to cement the joint. (Yes, it’s a cheap old iron that broke when it fell on the floor – in other words, perfect for use in the shop.)

When you’ve applied the whole length, trim the ends using a utility knife and a square or simply break them off. In either case, it’s best to leave a tiny nub that you can trim perfectly flush with the adjacent edge using a sanding block. Be sure to sand perfectly in line with the edge, not at an angle, to avoid rounding the corner over.

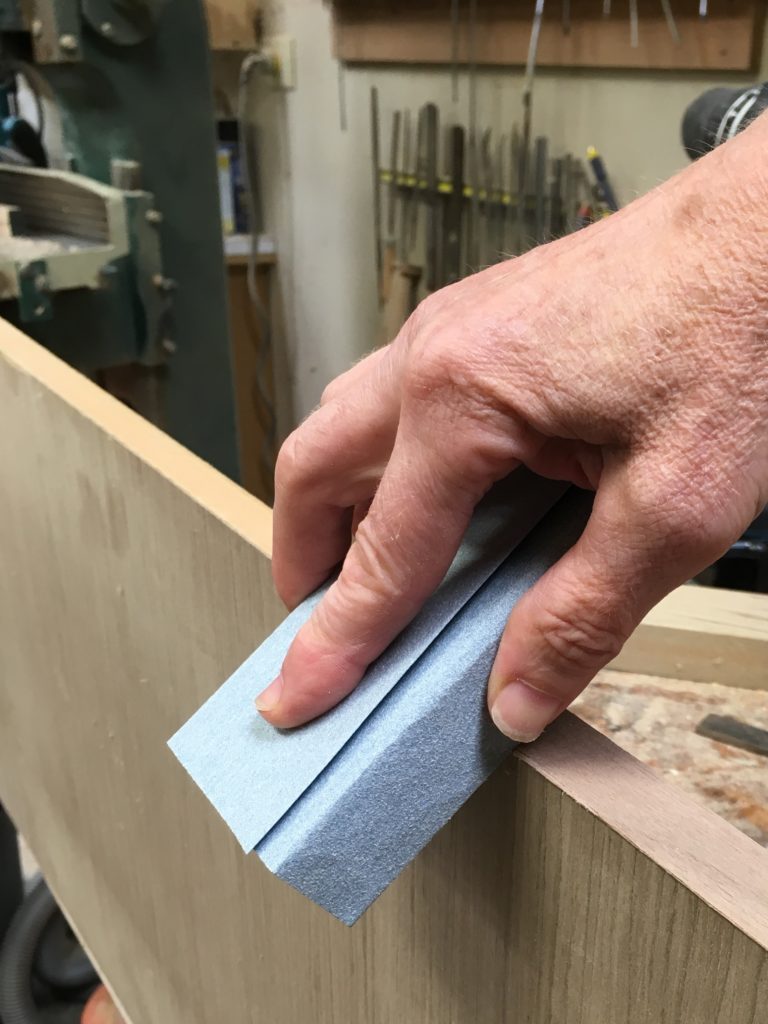

Next, trim the edges. There are various tools available for trimming, but my experience with the ones I’ve used is that they have a tendency to catch in the grain of the edge banding and cause tears. I’ve tried simply flattening the edges with a random orbital sander (lay the panel flat on your work bench, and hold the sander perfectly flat if you’re going to try this) but found it too easy to tear the veneer or even in some cases rip it right off. So in the end, I came up with the simplest low-tech method: I use the same sanding block as I use for the ends of the panel, but now at 45 degrees. As with the ends of the edge-banding, do not rub up and down; rub downward only. Otherwise you risk tearing the grain or even tearing the banding right off.

To trim the edges, hold your sanding block at 45 degrees.

As you sand through the waste veneer, you’ll produce a thin line of glue residue and wood fiber. Simply pull it off, as shown below. Don’t go on to the following step until you have removed this glue; any residue is likely to be spread onto the face of the panel, where — depending on the tone and figure — it may not be visible until after you’ve applied the finish. (Don’t ask me how I know this.)

As you sand through the veneer, you’ll end up with a thin line of residual glue. Simply pull it off. Don’t try to sand the face of the panel until after you’ve removed this glue.

Now that you’ve trimmed both ends perfectly square and both edges perfectly flat, finish cleaning up the face of the panel. Hold your sanding block perfectly flat and sand with the grain. Take care not to round over the corners of the edge-banding.

This method may be slower than using an edge-banding machine, but if you’re methodical and pay attention at each step, you’ll end up with a perfectly professional looking finish. This is the method I used to create the entire wall of matched panels at the opening of this post. You can see a cabinet refacing job I did several years ago using this method here.

This is a pantry cabinet refaced in teak composite veneer.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Some exquisite panels Nancy, such perfect detail and it looks oh so simple.

The pantry cabinet refaced in teak project, you have an edge veneer done as the same teek veneer wrapped around the corner. Wondering about your technique to wrap the corner and match the grain to the next panel.

Amazingly enough the ceiling looks to be the level and straight as well… no shortage of details…

Thanks and I am enjoying your blog posts!

Morgan