We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Quality counts. The combination square is one of the most frequently used tools in any project. Get yourself a good one, and chances are you will see a need for several more.

Choosing and using this must-have measuring and layout tool.

In 1878, Laroy S. Starrett designed and patented the combination square. His invention was a multi-purpose layout and measuring tool for machinists and it was rapidly adopted in the trade.

Woodworking books of the period don’t mention this tool. After all, the try square and marking gauge were common and effective, so it took a while for the transition from machine shop to cabinetshop. Today, most woodworkers own a combination square, but few know all of its uses, and many try to get by with inferior versions.

The biggest technical challenge Starrett faced was milling a groove that was perfectly parallel to the edges of the rule. That’s what allows the head to slide to any position and remain square to the blade. This is the part of the tool that most manufacturers still don’t get right. After 133 years, the Starrett square is still considered to be the best.

I use my combination squares to check corners and miters. It’s precise enough for that task, but I use it more often to mark, set, gauge and transfer precise measurements, both in the layout and in the making of joints. If the shop caught fire, I wouldn’t have to look for it as I ran out the door; it’s in my apron pocket or hand most of the time.

The adjustable square is also a great example of ergonomics, even though it was invented a century before the term became current. The curve in the stock is a comfortable place to park your thumb, or it nestles neatly in the crook between you thumb and forefinger. If you have any doubts about how to hold the tool, find a comfortable hand position and you can’t go wrong.

Size Matters

The combination square and its brother, the adjustable double square, come in several sizes, designated by the length of the rule. Four, six, and twelve-inch lengths are the useful sizes for the woodworker. The two I use most are a 6″ combination and a 4″ double square. These fit easily in an apron pocket and cover most common tasks.

Prices range from around $60 for the smallest to around $80 for the largest. That’s a tidy sum for a little bit of metal, but these are high-quality tools that last for generations. Every machinist who practiced the trade in the last century had at least one, so they are plentiful on the used-tool market.

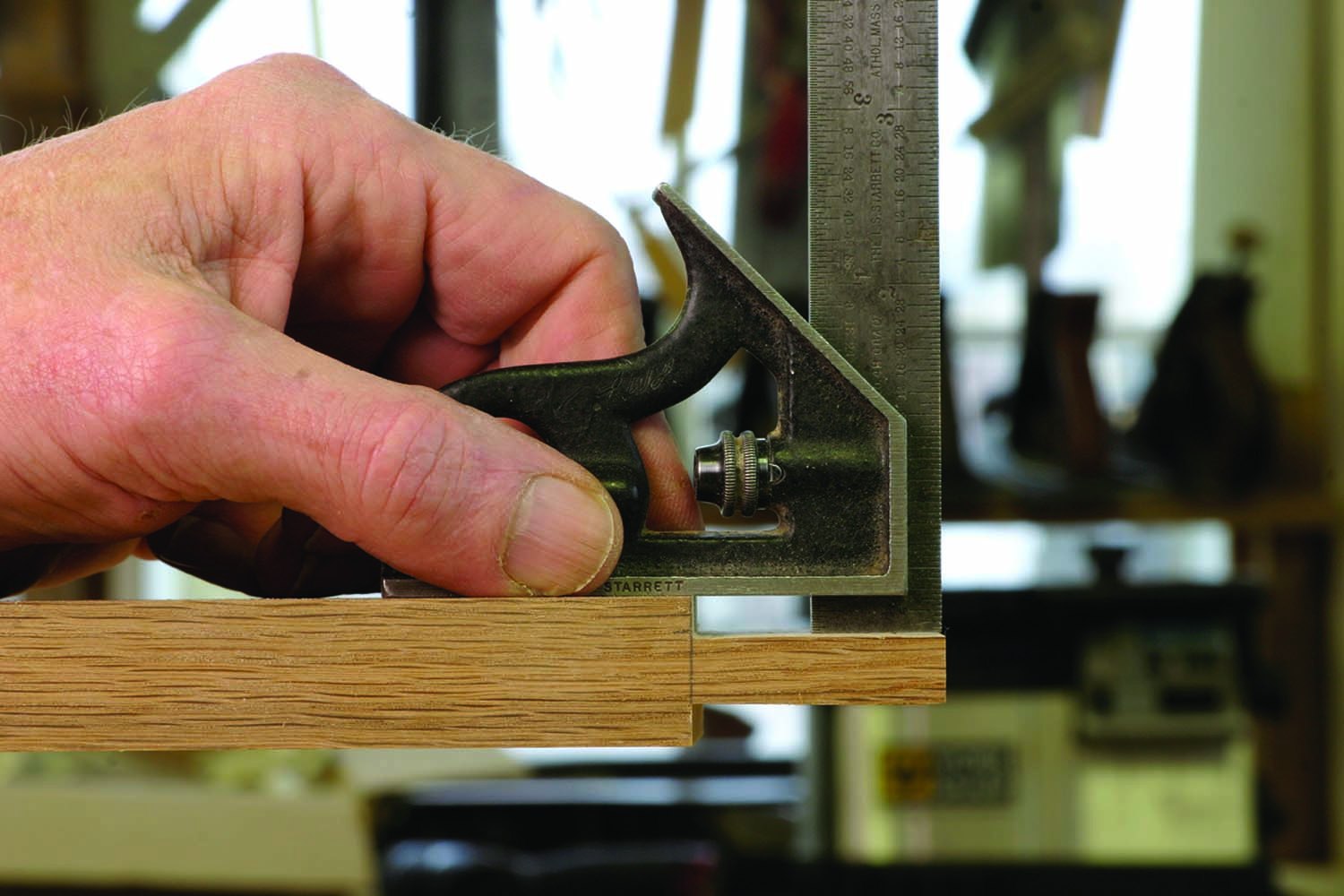

Like a glove. The head of a good combination square fits comfortably in the hand, in almost every usable position.

Don’t pay more than half the price of a new tool for an old one. In old tools, the level vial and small metal scribe are often missing. Use that as a bargaining tool to get a lower price (you won’t notice their absence). Parts are generally interchangeable and available; if you find a usable head you can get a rule for it, and you can replace a broken lock bolt.

When you shop, you’ll see two additional heads: a center-finder and a protractor. You may be tempted to get these, but in all likelihood you can live without them. I inherited my grandfather’s tools, and the protractor and center-finding head have been in the same drawer for the last 20 years.

The heads are available two ways: cast iron or hardened steel. The steel costs about $10 more and is more durable. The cast head will still last several lifetimes, and a smooth file and a few minutes’ effort will smooth out minor dents and dings in the cast head.

Pencil’s partner. Make a parallel line a precise distance from an existing edge by sliding the head along the work and holding a pencil to the end of the rule.

It may be painful to pony up the cash for a Starrett, but that pain will go away and you won’t have any regrets after you start using one. There are a couple other brands that are close in quality; Browne & Sharpe and Mitutoyo are well regarded, and Lee Valley has a very nice double square in 4″ and 6″ sizes for a bit less money than a Starrett.

The cheap imitations you see for half the price or less are, well, cheap imitations. That kind of tool will hurt every time you try to use it. If you only splurge on one tool in you life, get a Starrett square. You’ll be glad you did every time you pick it up, and your children and grandchildren will inherit a valuable and useful tool.

Follow the Rule

There are also options for the graduations on the rule. The most common is called 4R. The 4R scale is in inches and fractions (as it should be) with one edge marked in 1⁄8” increments, with the opposite one in 1⁄16“. Flip the rule over and it is marked in 1⁄32” on one side and 1⁄64” on the other.

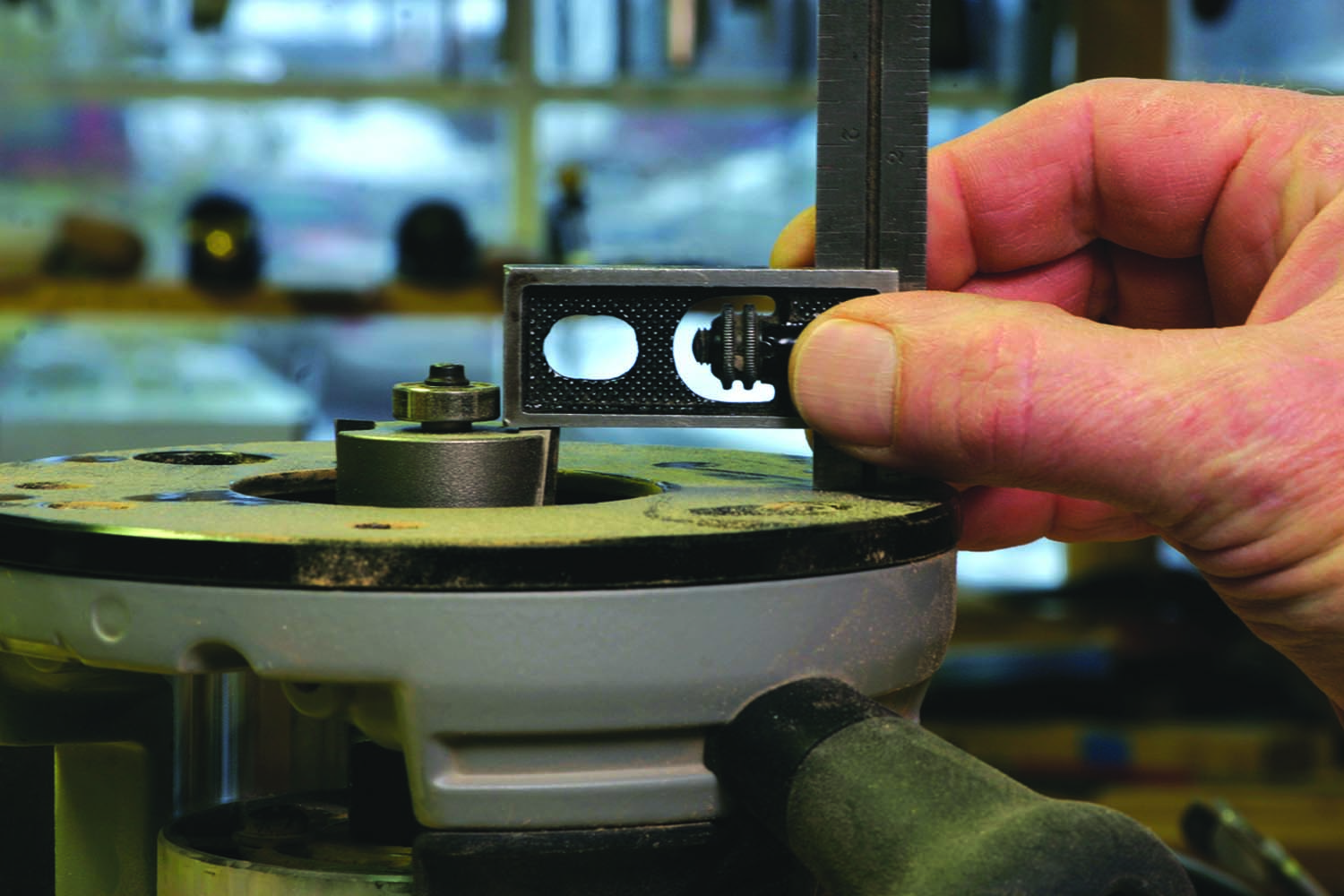

Remove & reverse. The groove in the rule slides in a tongue at the end of the spring-loaded reversible lock bolt. If you remove the rule, you need to line them up.

Scales in other formats are available. If you work in the metric system you can get a rule divided in millimeters, and you may find an older rule divided into 10ths or 50ths of an inch. You can always buy a replacement rule with the 4R graduations.

The larger divisions are on the side of the rule with the groove, and I work most of the time with the groove up. I rarely need to set a distance finer than 1⁄16” and when I mark with a pencil from the end of the rule, the pencil point won’t slip into the groove.

There is a solution. The rule rides on two nubs inside the head. If it isn’t square, filing one nub or the other will bring it back.

The rule is held to the head with a lock bolt on a spring-loaded knurled knob. A tongue on the end of the bolt fits in the groove, and when you tighten the knob, this holds the rule against two raised nubs within the head. If the square ever goes out of alignment, you can get it back in by carefully filing one of the nubs.

To fit the rule to the stock, push in on the knurled knob and turn it to align the tongue with the groove. It’s dark in there and hard to see, but you can reverse the direction the rule extends from the head by turning the post 180˚. Wipe the rule once in a while with some light oil to keep it sliding smoothly and free of corrosion.

Light the way. Hold the square and your work up to a light source and you can detect tiny variations. Here, there aren’t any.

To use the square to check an inside corner, loosen the knob and set the bottom of the rule down on a flat surface, such as the top of your table saw. This ensures that the rule is not extending past the head.

To check an outside corner, hold the square against the end of the board and aim that at a source of light. Check a 45˚ miter the same way. Teeny-tiny discrepancies will show as a band of light between the metal edges of the square and the wood.

The Good Part

Checking corners isn’t anything special, and you don’t need to spend a lot for a tool that is capable of that task. If that’s all you need, you can get an imported engineer’s square for $10. Where the combination square and the adjustable square become heroes is when you make use of the sliding rule.

Most joint layout involves making a line parallel to an existing edge. Adjust the rule to any dimension from the bottom of the head and hold the head against an edge. Place the point of your pencil against the end of the rule and slide the square along the edge, keeping the pencil in place. The result is a parallel line. This works along convex curves just as easily as for straight lines.

Don’t touch that dial. A setting from your layout can also be used to set cutters to an exact distance.

Want to make a rabbet in the end of a board that matches the thickness of another board? With a fixed-head square, you have to measure the thickness, then carefully measure from the end and make your mark. If you’re good at measuring and really careful you can come pretty close, but it will take a while.

With an adjustable square, you can set the first piece on your bench, set the bottom of the head on top of it, loosen the knob and drop the end of the rule down on the benchtop. Tighten the knob and move on to the other board. Place the head of the square on the end and mark from the end of the rule.

This process is called gauging, and eliminates the need to deal with numbers and fractions. A piece of wood that should be 3⁄4” may actually be 25⁄32” or 49⁄64” – but that won’t matter. Because you set the distance from the material you know you’re right and the parts will fit. Not only are you right but you’re finished in far less time than it would take to squint and decide which itty-bitty mark is closest.

Check your work. After you make a cut, you can check to see how close you came to your layout lines.

You can use this trick to match one element of a joint to another. Drop the rule down into a groove, or down the shoulder of a tenon, and transfer the exact size to the matching part. You can use the same square you used to make the mark to set up your tools. Then, when you cut the parts, you can use the pre-set square to check your work.

You can also find the precise center of board in a similar fashion. Draw a square line anywhere across an edge, then mark a 45˚ line starting at the corner of the line and the edge. Flip the square over and draw a second 45˚ line from the opposite corner. The two lines will make an “X” and the intersection will be at the exact center of the edge.

“X” marks the spot. Use the 45˚ head to find the exact center by drawing angled lines from opposite edges. Where they meet is dead center.

Place the bottom of the head against the edge, and set the end of the rule to the intersection and your square is now set to mark the centerline of your stock. Make a mark from both sides and draw a pencil line parallel to the edge, through the center of the “X”. Mark from both sides to be sure you’re right.

If there is a gap between the two lines, you’re off a little bit, or you need to adjust for the thickness of your pencil line. Aim the end of the rule for the center of the gap and readjust. When the two lines coincide, your line is dead center, and you didn’t have to divide 49⁄64” by two. If you want to find the center of a square piece, eyeball the center and mark in from all four sides. A tiny square in the exact center will be the result, even if the stock isn’t perfect.

Repeat After Me

It’s handy to be able to keep a distance setting throughout a project, and this is a valid reason for owning more than one adjustable or combination square. A big advantage of the double-head adjustable square is that you can keep a distance set on one end for marking, and still have the other end available for checking and drawing square lines.

You can also use an adjustable square to mark repeating distances along a line, such as a row of regularly spaced holes for shelf pins. Set the center-to-center distance and make a mark at the center of the row to start. Then set the edge of the head on the mark and make a second mark from the end of the rule.

You can continue on indefinitely, and if you are spacing parts, you can set one square to the size of the part, and a second square to the size of the gap. Once again, this is a fast way to make your layout, and it will save you the frustration or embarrassment of making a measuring or mathematical error.

Parts of the square itself can be used to mark common dimensions. The rule on the 6″ Starrett combination square is 1⁄16” thick and 3⁄4” wide. On the 12″ square, the blade is 1″ wide.

Fast & precise. Make a series of accurately spaced marks by lining up the end of the blade with the last mark made.

The knowledge of when and how to use the sliding head is the key to the tool’s versatility and precision. Much of woodworking is simply cutting to a line. With a good adjustable square, getting good lines in the right places is simple matter.

A good square will also improve your accuracy, and provide you with a reference that you can rely on with confidence. It’s also an inspirational tool; it reminds you that accuracy is important in all phases of woodworking. If you can work up to the level of the quality of the tool, you’ll have nothing to be ashamed of in your woodworking.

Video: Learn how to fix a combination square when it’s out of square.

Web site: Visit the L.S. Starrett web site for history and a full catalog.

To buy: Shop where the machinists shop at McMaster-Carr.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.