We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Inside Greene and Greene Furniture

How teamwork between architects and woodworkers solved classic problems in furniture design.

By Tom Caspar

| Here’s a recipe for creativity: Mix two gifted architects with two seasoned woodworkers, throw in a bunch of money and shake. The result can be a huge step forward in practical furniture design. That’s exactly what happened in California just before World War I, when architects Charles and Henry Greene worked with cabinetmakers John and Peter Hall building houses and furnishings for wealthy Pasadena clients. As a team they solved problems of wood movement, weak short grain and efficiencies in production that had plagued woodworkers for generations. |

| The look of Greene and Greene furniture has captured the imagination of many of today’s furniture makers. For me it’s the guts that are really fascinating. What holds this furniture together? What’s the story behind the innovative construction techniques?

Recent X-ray photographs published by Professor Edward S. Cooke, Jr. of Yale University have cleared up a lot of misconceptions about how this joinery actually works. In addition, interviews by scholars with descendants of the immigrants who worked in the Hall’s shop reveal that many of the Greene’s construction ideas actually came from Scandinavia. Let’s take a closer look at some of the best-known furniture designed by Greene and Greene for lumber baron Robert Blacker in 1908. By this time the collaboration between this group of architects and woodworkers had fully matured. The Greenes had taken on ambitious commissions to design houses and furnishings in a completely new style from top to bottom. The Halls had built a millwork production shop equipped with large line-shaft machinery where the techniques of making multiples efficiently and quickly were well known. Charles Greene, who specialized in furniture, set up a workbench for himself in the Hall’s shop. He worked alongside seasoned cabinetmakers who had apprenticed in Scandinavia. Here are three examples of the design problems they tackled.

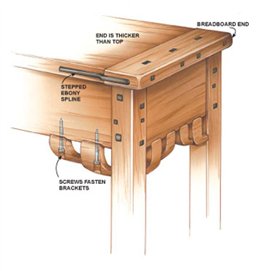

Wood movement and breadboard endsBreadboard ends have stymied furniture makers for generations. They’re meant to keep a top flat and cover up porous end grain. But they also invite disaster because the grain of the breadboard end, or cleat, runs opposite to the grain of the top. A top should be able to freely expand and contract, but a mortised and glued cleat will restrain it. Something has to give and inevitably the top cracks. A second tricky situation involves flush joints, a favorite of meticulous artisans. A breadboard end originally made flush with a top won’t remain even as the top moves. Usually the cleat ends up sticking out, marring the original clean lines of the table. The Greenes and Halls worked out solutions to both problems. Their breadboard ends don’t restrain the top. They’re joined to the top with a tongue and groove joint that isn’t glued and screws that pass through slotted washers. As the top expands and contracts the screws move back and forth through the washers. An ebony spline at the end of the cleat both strengthens and covers the joint. A Greene and Greene breadboard end is never flush with the side of the top. That’s their solution to the clean line problem. They substituted stepped surfaces for flush ones. You’ll hardly find any flush joints in Greene and Greene furniture. Every surface lies on different levels. That’s both a design statement and a concession to making furniture easy to build. They were early masters at what we now call a “reveal.”

Short grain and splined jointsChair arms get a lot of hard use. Every time you push yourself out of a chair you put enormous strain on fairly thin members. It’s not unusual for an arm to break near the joint. The short grain in a continuous arm is particularly weak, so Charles Greene strengthened the joint with ebony splines. From the outside the splines appear to be one large piece of wood reinforced with square pegs. The joint between arm and post looks like one very large bridle joint. But it’s not. X-ray photographs reveal that the joint is actually standard mortise and tenon work (Fig. E). The spline is composed of narrow strips of ebony sitting in shallow grooves. Furthermore, the plugs are only decorative. There are no screws or dowels behind them. They merely add the appearance of strength by simulating the rivets of steel girders.

Production work and drawer joineryYou won’t find dovetails in Greene and Greene furniture made by the Halls. They used machined joints that didn’t require laborious handwork. They valued efficiency of production more than virtuoso cabinet making. But they were able to take humble joints and transform them into works of art. In this composite of two different drawers, you’ll find joints that were made on the tablesaw (Fig. F). Neither joint was commonly used at the time on high-end furniture. The half-blind tongue and rabbet probably was an innovation introduced by the Hall’s Scandinavian-trained furniture makers, according to Professor Cooke. Many Greene and Greene drawers were center-guided with a track running underneath the middle of the drawer bottom. It’s a production shop method that may well have been a Scandinavian innovation, too. Center-guided drawers have three advantages over conventional drawers. First, they are easier to fit into a case. The sides are set back from the front, so they don’t have to be planed down. Only the thin ends of the drawer front must be fitted. Second, once a batch of center guides is machined and installed, each drawer will run smoothly right off the bat. Conventional drawers, on the other hand, require a great deal of individual attention. Third, a drawer guided in the center is easy to pull out with one hand because it doesn’t rack. Sources(Note: Product availability and costs are subject to change since original publication date.) Our thanks to Dr. Edward S. Cooke, Jr. for his research, which was published as ‘Scandinavian Modern Furniture in The Arts and Crafts Period: The Collaboration of the Greenes and Halls’ in the book “American Furniture, 1993,” University Press of New England (out of print). For more information on the furniture, see “Greene and Greene, Furniture and Related Objects,” by Randell Makinson, 1983, $24. For a closer look at details, see “Images of the Gamble House,” by Jeanette Thomas, 1995, $20. Both books are available at www.amazon.com. This story originally appeared in American Woodworker February 2000, issue #78. |

Click any image to view a larger version.

Fig. A: Writing Desk Designed by Greene and Greene for the Blacker House circa 1910: The work of two important Arts and Crafts designers was a marriage of artistry and production-shop woodworking.

Fig. B: Bench for the Blacker House: The grain of the top and breadboard end run in opposite directions. Greene and Hall joinery allows the top to move freely, so it won’t crack.

Fig. C: Exploded View of Breadboard End: Screws buried under wood plugs hold the end onto the top. A spline covers the tongue and groove joint.

Fig. D: Armchair for the Blacker House: A continuous arm is easy to break, but this one is reinforced with ebony splines.

Fig. E: Exploded View of Splined Joint: Two splines strengthen the short grain and bind the arm to the post.

Fig. F: Two Styles of Drawer Joints: Production shop joints, not dovetails, hold these center-guided drawers together. |

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.