We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Coved Doors on the Tablesaw

Make beautiful raised panels without a router table and expensive bits.

By George Vondriska

|

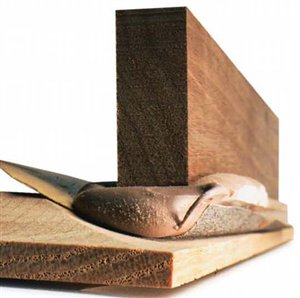

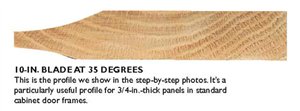

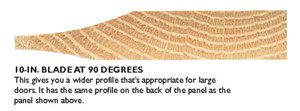

The tool of choice for most small-shop woodworkers who want to make raised panels is the router: A large one, generally 3 hp,hung in a router table, plus a set of specialized bits. But what if you just want to make one or two raised-panel doors, say for a bathroom vanity, a small cabinet, or a jewelry box? With our technique you can make raised panels with the traditional scooped-out profile using just your tablesaw. This process is based on the traditional method for cutting coved moldings on the tablesaw, but we’ve adapted it for making raised panels.You clamp an auxiliary fence at an angle to your blade, and feed the panel over the blade repeatedly, taking off only a little at a time until you get the profile you want.Cutting coves on the tablesaw can require a fair amount of trial and error,but we’ve eliminated that by developing a simple recipe that steers you through the process and gives you perfect results, even the first time. For large doors, cutting coved panels on the tablesaw is actually a better technique than using a router.The tablesaw allows you to cut a very wide profile; wider than you could cut with a router bit. On large raised panels, like those found on entertainment centers and armoires, the narrow profile produced by router bits can look out of scale. The best way to cut these wider raised panels is with a shaper,but again, if you’re only making a couple panels, this tablesaw method will give you excellent results. For many doors, you may still need a router and a railand- stile router bit set to make the door frames. But these are smaller, less-expensive bits, and don’t require a 3-hp router. The bad newsOne downside of this tablesaw technique is that the panel requires a The other drawback to this technique, although it’s minor, is that

What you needAny tablesaw, from benchtop to cabinet saw, can handle this work, as You’ll need to build a simple auxiliary fence for your tablesaw and a

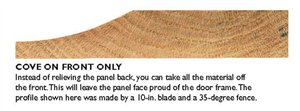

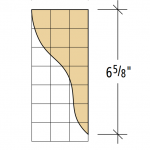

Planning your doorsWith this method, the panels are cut to fit the frame, so it’s Glue up your panels, if required,and plane them all to the same By varying the angle of the fence and the size of the blade you use, For our doors,we planed the panels to 13/16-in. thick, and cut a

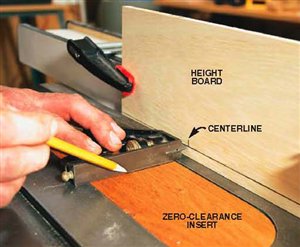

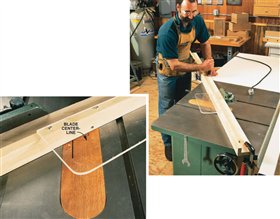

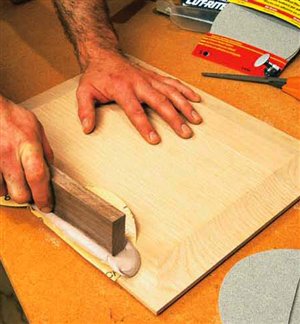

First, set up your sawThe actual cutting of the panels is fairly straightforward; you clamp a fence at an 1. First,build the auxiliary fence (Photo 3) and make the centering 2. Find top-dead-center of the blade using the centering board and 3. Transfer the location of top-dead-center to your zero-clearance 4. Position the fence on the tablesaw so it covers the front half of the blade,where the teeth point

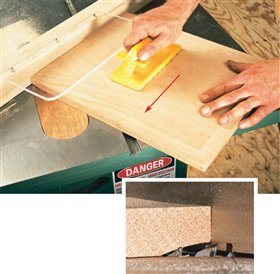

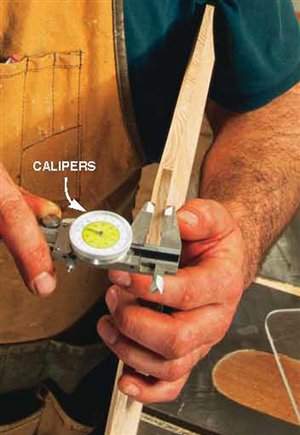

Cut the coved profileNow that your fence is set, it’s time to actually cut the panels. Here’s the process: 1. Raise the blade 1/16-in. above the surface of the tablesaw and cut 2. Increase the height of the blade 1/16 in. and make another pass on 3. Finish the front of the panel by continuing to raise the blade 4. Measure the thickness of the panel tongue (Photo 7). Leave it

Sand the profileTo sand the saw scratches out of the profile without spoiling its When you sand the profile, start with 80-grit sandpaper and move up

Tips for great coved panelsRaise the blade in small increments; 1/16 in. at a time. Light passes Have on hand an extra panel, of the same dimensions and thickness

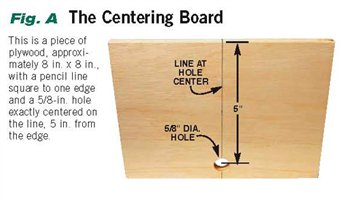

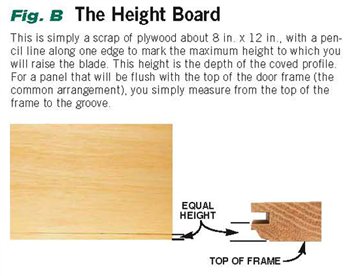

Oops!We learned the hard way that setting up the fence carefully is essential. If the auxiliary fence is located behind the center of the blade, you’ll get a profile that gets thicker right at the edge. This won’t fit into the groove worth a darn. Use the setup procedure we show, and you’ll be sure you’ve set the fence at the top-dead-center of the blade. Sources(Note: Product availability and costs are subject to change since original publication date.) Auto parts stores, Auto body filler. Highland Hardware, 800-241-6748, Fractional dial caliper, Home centers, Self-adhesive sandpaper, 6" discs. Woodworker’s Supply, 800-645-9292, Push Block. Fig. A: The Centering BoardFig. B: The Height BoardThis story originally appeared in American Woodworker September 2002, issue #95. |

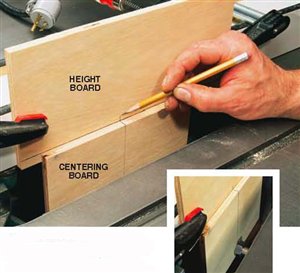

Click any image to view a larger version. 1. Locate the center of your saw arbor. Mount the centering board on the arbor as if it was the saw blade, and clamp the height board to the rip fence, with the bottom edge at the level of the saw table. Raise the arbor of your saw until the top of the centering board is at the line on the height board. Mark where the arbor line meets the height line. 2. Transfer the centerline from the height board to the zero-clearance throat plate.Then raise the blade to the maximum height you will be using, while the zero-clearance throat plate is clamped down. 3. Clamp a shop-made fence to your saw using |

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.