We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Wayne Duguay of Vancouver, British Columbia, works on his dovetailing skills at Rosewood Studio, a school that emphasizes both machine and hand skills.

This Canadian school has its roots in the College of the Redwoods.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the August 2004 issue of Popular Woodworking. Christopher Schwarz visited Rosewood again in 2013 at their new location in Perth, ON, where it still exists today.

The photographic image of cabinetmaker and teacher James Krenov looks down from the door of Robert Van Norman’s tool cabinet as he carefully pulls out the planes, spokeshaves and chisels he has fashioned to build chairs and cabinets of his own design.

Picking up the rear post of a chair from his bench, Van Norman matches the sole of a wooden compass plane to the inside radius of the dramatically curved piece of wood. What is immediately apparent by this simple act is that the plane has been made with as much care and skill as the post. Chip-carved into the stock of the plane are a series of small depressions on the sidewalls and on the top of the tool’s toe. Though the carvings are indeed decorative, they also allow the user to grip the plane with remarkable force. The tool feels like an extension of the woodworker’s arm.

“Toolmaking is an important part of what we do here at Rosewood Studio,” says Van Norman, an instructor at the Almonte, Ontario, school. “We get into metalworking a little bit here – it helps the woodworking.”

There’s little doubt that Krenov, the former head of the fine woodworking program at the College of the Redwoods in Fort Bragg, Calif., would be pleased with the direction of this woodworking school outside Ottawa. Both Van Norman and the school’s founder, Ted Brown, are graduates of the College of the Redwoods and have transplanted Krenov’s approach to woodworking from the rugged landscape of Northern California to the windswept hills of eastern Ontario.

Machines Mix with Hand Tools

The high ceilings, huge windows and white walls of the bench room create an environment that is awash with natural light and peaceful. No machines are allowed in here.

Rosewood is located in a cozy village at the back of a restored mill along the Mississippi River. The school caters to the woodworker who is looking for a weekend or week-long class, as well as to the more-serious individual who is considering making a living at the craft and is willing to devote 12 weeks to it.

Like the teachers at the College of the Redwoods, the instructors at Rosewood teach a blend of machine skills and hand skills – the machines handle the brutal work of fabricating furniture parts; the hand tools are used for the joinery and details, Van Norman says.

“The majority of the refinement of a piece is done with hand tools,” he says. “We don’t have really sophisticated equipment.”

Sophistication, of course, is in the eye of the beholder. While it’s true that you won’t see a lot of gee-whiz dovetail jigs on the shelves, the primary machine room at Rosewood is impressive. Rough stock is broken down on a General 12″ jointer and a 14″ heavy-duty planer. In the middle of the room is a 20″ Northfield band saw with a rip fence. At the other side of the room there’s a General cabinet saw set up only for crosscutting with a shopmade sled and an Excalibur overarm guard. A Wadkin shaper, Excalibur scrollsaw and Rockwell lathe round out the machinery housed in this center room of the school.

A second machine room is filled with smaller heavy-duty equipment: another General planer, a Delta 161⁄2” drill press, a Davis & Wells horizontal boring machine, a Felder mortising machine, a Wadkin 9″ jointer, a General 690 band saw, a Unisaw, a router table, a small Performax drum sander and a cabinet filled with hand power tools.

A Sharpening Session

Will Rafferty of Rhode Island practices his sharpening skills as he tunes up a chisel.

On a recent Saturday morning, however, the machines are mostly quiet. Student Tom Masirovits heads to the jointer at one point, but it is to flatten the sole of his smoothing plane with the assistance of a strip of sandpaper and the machine’s long bed. Three other students are sharpening chisels and plane blades. The only sound that rises above the rushing rapids outside the tall windows is the occasional “hum” and “grrr” of a Baldor grinder as it shapes another tool’s bevel.

Doug Wing, a student from Montana, sharpens a plane blade on a waterstone and checks his progress. He’s at the beginning of Rosewood’s 12-week intensive course, something he left a job in Antarctica to pursue.

“I want to make my own furniture when I finish,” he says, frowning a bit at his plane iron and returning it to the waterstone. “Then I’ll see what happens.”

Will Rafferty, a student from Rhode Island, chimes in. “I’ve always chosen careers that don’t make much money,” he says. “But with this – woodworking – you have something to show for it at the end of the day.”

Van Norman says this is typical for the students who attend the 12-week course. Many are interested in pursuing a career in building furniture, though the instructors are realistic about the risks.

“We caution them that 12 weeks is not enough to make you a pro,” he says. “But it depends on where you are as a woodworker when you begin the course. Some of these people are new to the craft and some have 30 years experience building cabinets.”

Once a mock-up is complete (such as this one), the student can make the full-size drawings necessary to build the project.

Some people are beginning to take notice of the skill of Rosewood’s graduates. Vicki Rosenzweig, who completed the 12-week intensive course, was hired by Paul Down Cabinetmakers in Bridgeport, Pa. And graduate Michael Mulrooney works in Ed Krause’s shop in Minneapolis, Minn., and teaches at the Wild Earth School in Hudson, Wis.

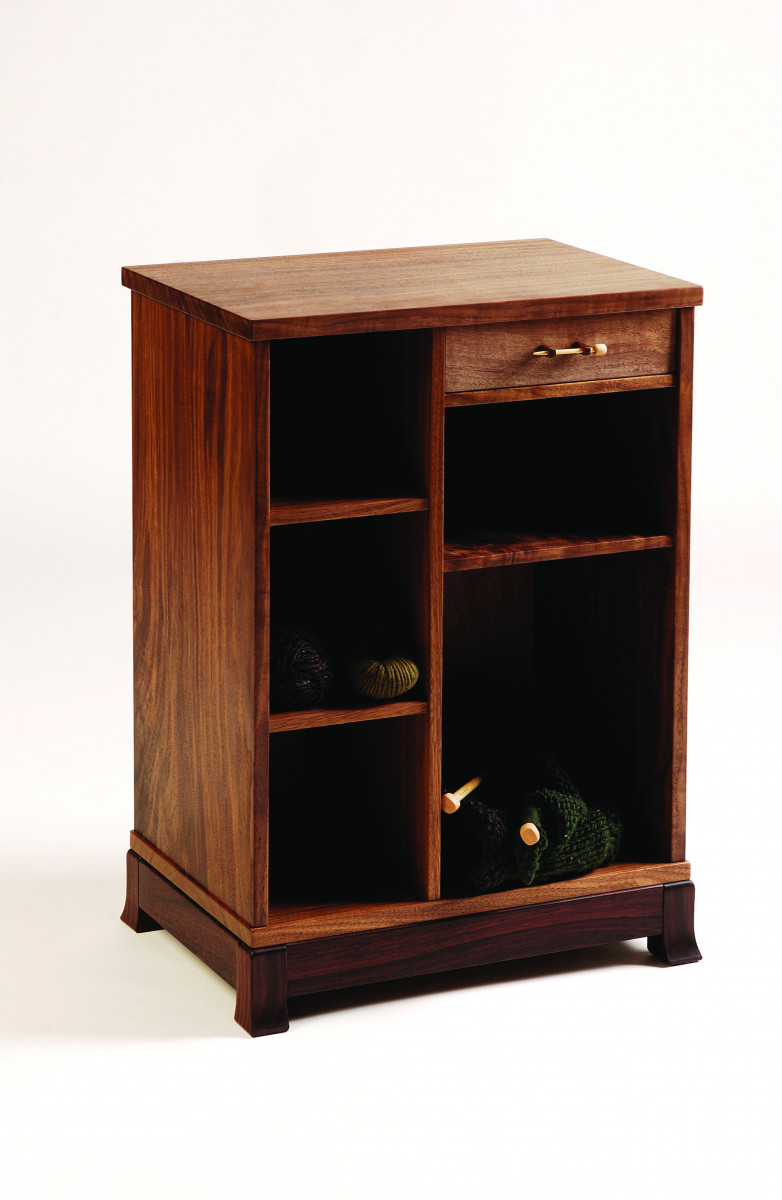

This walnut and rosewood knitting cabinet was built by graduate Vicki Rosenzweig.

But many of the students who pass through the doors of Rosewood are there for the shorter courses taught by the school’s faculty and a rather impressive roster of visiting woodworkers – Garrett Hack teaches there regularly about hand tools; Chris Pye teaches carving; Yeung Chan teaches joinery.

The students come from all over the world. Americans in particular have benefited recently from the Canadian exchange rate. (For example, the $7,900 tuition in Canadian dollars for the 12-week course translated to less than $6,000 in U.S. dollars in March. A one-week course costing $800 Canadian was $607 in U.S. dollars – a good value.)

The Peaceful Bench Room

Making your own tools is one important part of the curriculum for the students in the intensive 12-week course at Rosewood.

After the students get their tools sharp, they move to the bench room, an “L”-shaped room that wraps around the primary machine room. Machines are forbidden in this room, which has high white walls and large windows that look out on the river. Fifteen European-style workbenches line the walls with a cabinet above each for the student’s tools.

Today the students are practicing dovetailing with a gent’s saw or are tuning up their smoothing planes to true up a maple board.

Fred Ingram from Perth, Ontario, constructed this bubinga and sea grass hall bench at Rosewood.

The room is relatively quiet, and one of the students gazes out the window for a few peaceful moments before returning to the maple on his bench. Another student scurries off to the bakery a few doors down for a cup of coffee and a warm pastry.

In a few weeks, these students will build a piece of furniture using the skills they are learning today. First they will make a rough sketch. Then they’ll build a mock-up using 2x4s and cardboard. They might even have to make full-size drawings.

Instructor Robert Van Norman’s tool cabinet is filled with tools he has made or modified during his career as a woodworker.

It sounds like a lot to accomplish. But the most important lesson they’ll learn, Van Norman says, is to avoid rushing a project.

“One of the things we stress here is slowing down and working on the details,” he says. “That is what really makes a piece. We talk about production work. We show them how to efficiently do multiples and make jigs for repeating complex operations.

“But what we focus on is how to make one-of-a-kind pieces.”

This French walnut table was completed by student Rotem Almagore of Tel Aviv, Israel.

Van Norman, a professional woodworker for 17 years, finally pulls out a small wooden plane from his cabinet that has an exotic-wood sole. This plane, he explains, was made for him by Krenov. He places it next to a set of astonishingly tight and curved dovetails he cut recently, then looks up from his bench.

“I really like watching the students develop,” he explains. “James Krenov would be the first to tell you that we spend a lifetime learning (woodworking). And now I’m here helping students at the beginning.”

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.