We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

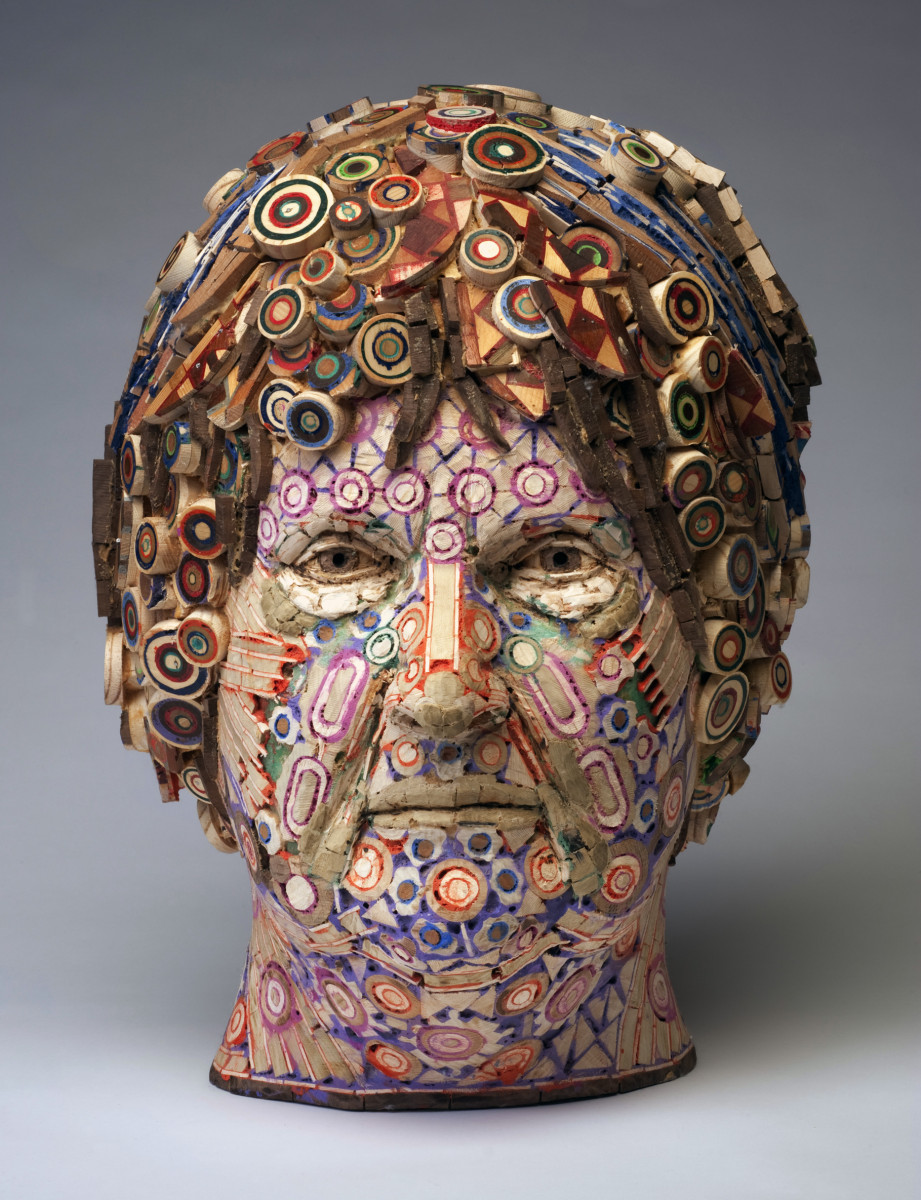

Maria, 2008-2009

A look into the larger-than-life.

Sometimes inspiration comes from the strangest places. Take a tree stump bust and an inlay backgammon table for example. Two very different woodworking mediums that couldn’t be further apart, but for artist Michael Ferris it’s the original source of his unique sculptures. His father, who was Lebanese had a pair of Syrian mosaic backgammon tables, and both his parents had outsider busts carved from tree stumps. Michael remembers looking at these items frequently as a child, soaking in all of the details. “My work is in a way a combination of both those two pieces. That’s really where this interest came from.”

Michael Ferris opened his first solo exhibition on the east coast this past November at the Center for Art in Wood. For those not familiar with his work, it’s a 3-D intarsia of sorts, often on a large and complex wooden canvas so to speak. The subject matter is almost always human portraits, and the execution is almost abstract or surreal- from a distance they appear almost lifelike, and as you get closer the details and colors pop with complex patterns and layers.

Michael works in a much larger-than-life scale for his sculptures.

The Journey

The use of color is a bit of a peek back into Michaels artistic journey; before he was a sculptor, he had studied to be a painter. He even completed his B.F.A. and M.F.A. in painting from the Kansas City Art Institute and Indiana University-Bloomington respectively before wholly committing to sculpture. “I was getting my master’s degree at Indiana in Bloomington, I started making these wood sculptures. And I would make them at my home, and I didn’t really show my professors for a long time (…) and they were receptive, they were positive, and so then I just continued from that. It really became the main type of artwork I make.”

His early work was fairly introspective: “they were sort of self portraits; they didn’t quite look like me, I considered them self portraits. I gave them names of other people, so I didn’t call each one a self portrait.” Over time the inspiration changed, and now he makes busts of other people in a larger-than-life scale.

Toufic, 2010.

The Process

Michael exclusively uses offcut pieces of wood in his sculptures. “There was so much wood that was being discarded that I could make entire sculptures and not have to purchase any wood (…) it’s basically garbage that I’m reclaiming and attempting to make something beautiful from.” He collects it from various woodshops on the east coast, and only uses the wood he has on hand when creating his work.

The sculptures themselves start with a wood armature, or framework, that Michael then laminates with several layers of pine before sanding and shaping. Once the overall shape is defined, he starts the mosaic layering on top of that. The pieces are cut into interesting shapes and assembly begins. Each piece is approximately 1/2″ thick, which allows Michael to go back later and continue shaping without cutting down to the laminate layer- unless he wants to that is. As the piece is developed, certain parts may take on a high level of refinement, while others are sanded down bare. If it’s not turning out correctly, Michael doesn’t hesitate to fix it.

“Sometimes during the process the shape isn’t quite right and so I’ll sand away the mosaic (…) that really doesn’t bother me, reworking a piece, taking away a lot of hours that I had previously put into the piece is fine with me to get it something that’s better.”

Inside Michael’s studio.

A pigmented grout mixture with intense colors goes in between the individual pieces of wood, which is then sanded smooth again. At this point, Michael goes back with a drill and rotary tool to remove some material, then layer more mosaic shapes on top of that, adding to the intricate design.

The large scale Michael works with can create challenges. With only so much space in his studio at home, he has to plan in advance, designing the sculpture to break down into smaller pieces so it can be moved as needed. Careful planning doesn’t always prevent issues though. “I was awarded a studio in New York for a year (…) I made this gigantic head, and I measured and [thought] ok this thing will fit out the door, then realized it didn’t fit out the door. I had cut that sucker in half. (…) I managed to put it together later.”

Close-up detail from Toufic.

The Pandemic and Beyond

Like many of us, the pandemic shifted Michael’s job as a teacher to remote work. Thankfully for him, his studio is right in his own home, which gave him the opportunity to spend much more time on his sculptural work. “I was at home all the time, and it was actually very positive (…) I could spend a lot of time working on my work.”

This extra time allowed him to push himself for his then-upcoming exhibition, which was planned in advance of the pandemic. This included finishing up one of his most ambitious projects, Rosemarie, Ernest, and Stretchy. “That sculpture took more than two years to create (…) I don’t know if I would have been able to finish that piece [otherwise].” The final result was a six-foot-tall, 160-pound oversized statue of Rosemarie and her two even-more oversized cats.

Michael with Rosemarie, Ernest, and Stretchy.

After going with larger-than-life-sized sculptures throughout his career, Michael is beginning to shrink the scale a bit closer to real life. This has presented some new challenges, as his mosaic pieces have had to shrink as well. It’s given Michael the opportunity to look anew at his craft and approach. “I don’t want them to be simple, so it’s just a little bit more of a refined work… Which is interesting and fine, it’s good”

Michael’s exhibition Extra-Human: The Art of Michael Ferris is on display at The Center for Art in Wood until April 24th. You can also find him on Twitter @michael.ferris.sculpture

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.