We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

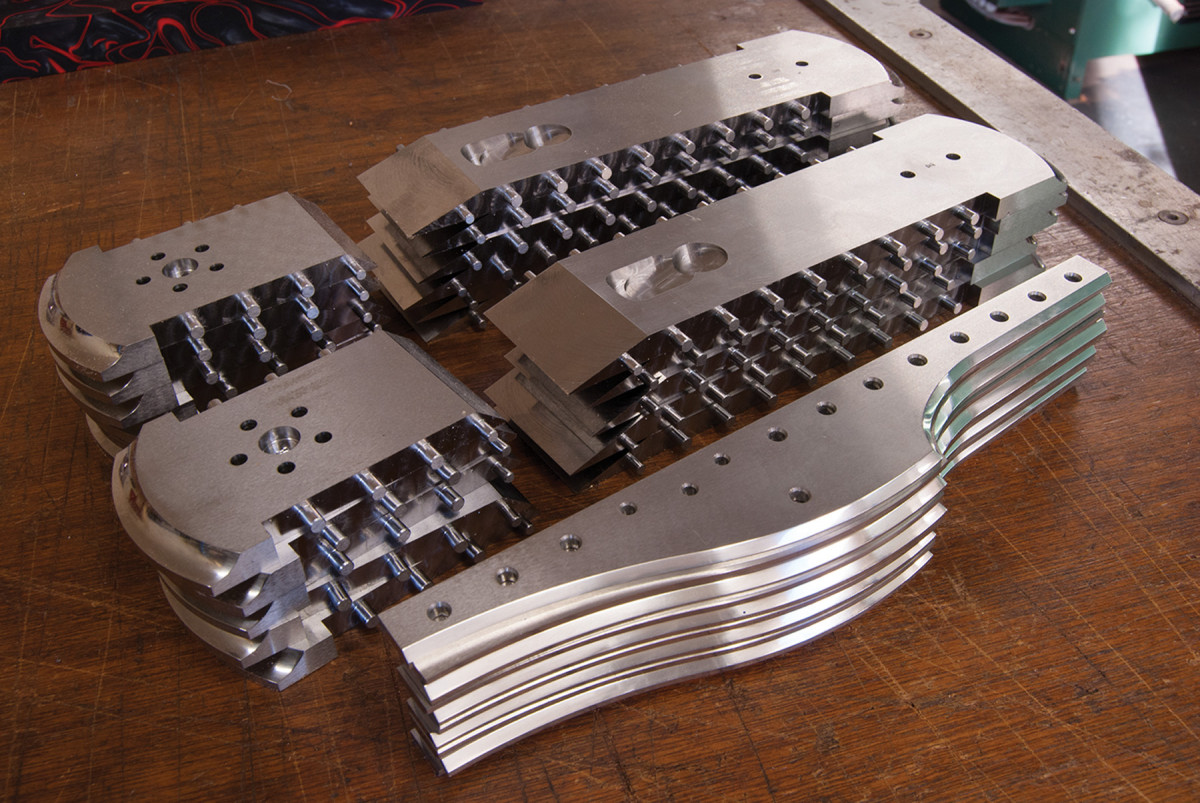

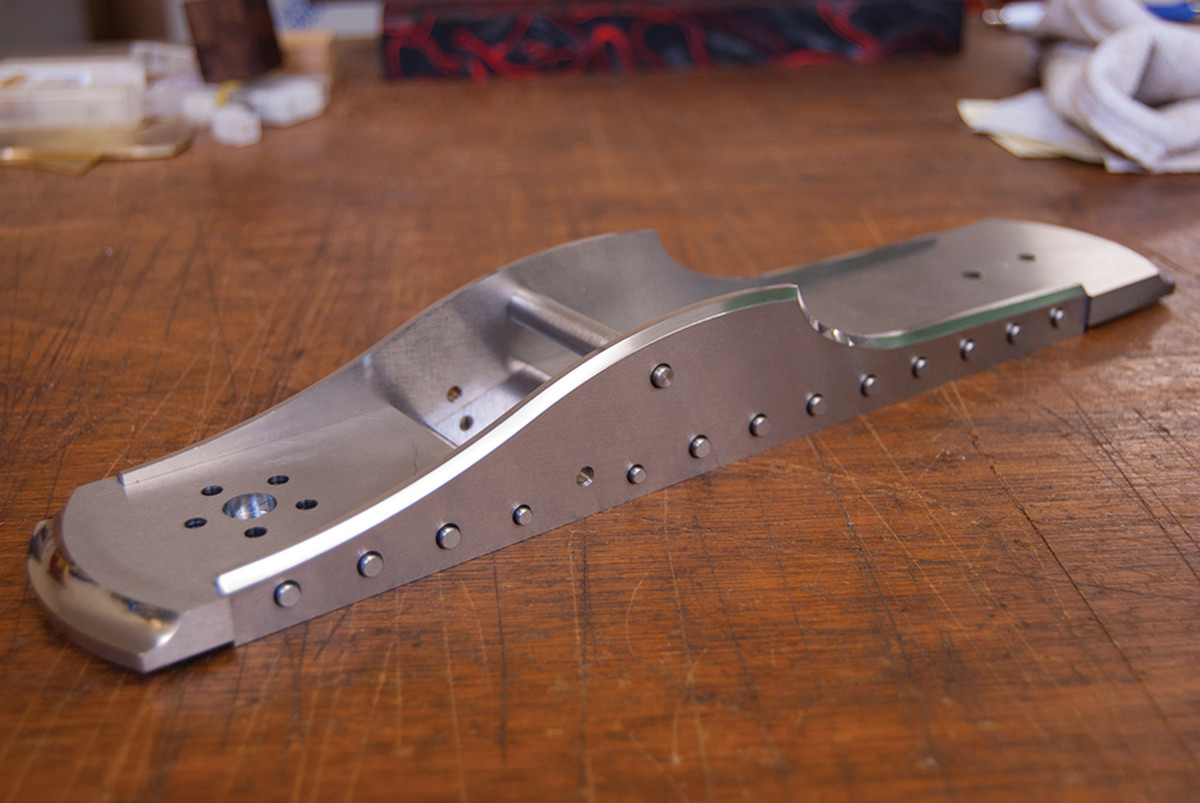

No. 983. Robin Lee convinced Holtey to develop the 983 block plane, show here in disassembled and complete form.

This legendary planemaker’s career has been dedicated to innovation.

There is no straight path between a childhood spent in a camp for displaced persons in Germany’s Black Forest at the end of the Second World War, and a workshop in the Scottish Highlands making some of the most desirable handplanes in the world. Nonetheless, that is the path that Karl Holtey (of Holtey Classic Hand Planes) has walked, and after only a few minutes of talking to Karl it is clear that his singular approach to planemaking is born of his equally unusual life. As Holtey nears the end of his final run of planes – the 984 panel plane – now is the ideal time to reassess his career and in particular the impact his innovations have had on modern planemaking.

Changing the Landscape

The innovator. Karl Holtey, of Holtey Classic Planes, pictured in his workshop.

While Holtey might not view his planes as perfect, his peers beg to differ. Planemaker Wayne Anderson characterizes Holtey as having “an ability to produce a plane with utter precision, like a Formula One race car [that is] second to none. When I first started planemaking, I printed several of his plane photos to remind me that perfection is an achievable goal,” says Anderson.

Nor have the benefits of Holtey’s innovations been confined to the purchasers of boutique infill planes. Holtey is widely credited in leading the way in utilizing alternative tool steels; Christopher Schwarz says, “there is little doubt that Karl’s efforts are what gave us the choice we have now” – particularly the now widespread availability of A2 steel blades. Similarly, Holtey’s work with bevel-up bench planes prompted a resurgent interest in such designs, culminating in the affordable line of bevel-up bench planes from Veritas. “If it weren’t for Karl, bevel-up tools would still be a backwater of aborted tool designs,” says Schwarz.

Given Holtey’s reputation as an innovator, it is no coincidence that in Robin Lee of Lee Valley/Veritas he has found a kindred spirit, with Lee prompting Holtey to develop the 983 block plane. During the two days I spent at Holtey’s workshop, he referred to Lee in warm terms and reflected on his visits to the Veritas manufactory, approving of the innovations Veritas has implemented. Through these conversations it became clear that although the consequences of Holtey’s innovations have impacted many of the major tool manufacturers, he considers Veritas to be continuing his work at a more affordable price point.

A Constant Prototype

Riveting. The integral rivets Holtey uses to join plane bodies are clearly visible in the first run of bodies for the 984 panel plane.

Holtey was born in London, England, in 1948 to an English mother and East Prussian father who had become a prisoner of war while serving in the German army during World War II. The social stigma of having married a member of the German military became too much for Holtey’s mother, who insisted the family leave England and move to Germany.

Life in Germany was not what she expected, and after four years living in a camp for displaced persons the family moved back to England and Holtey was placed in foster care.

Upon leaving school at age 14, he secured an apprenticeship with a French polishing company, which lasted for less than two weeks and involved more in the way of repairing roofs than it did in French polishing.

What followed was a restless period; another unfinished apprenticeship at an office furniture company, employment as a trainee watchmaker, building 30′ ocean sailing yachts and shop-fitting in the construction industry. Throughout this period Holtey found that his forte was in building prototypes rather than what he viewed as the “repetitive” work of cabinetmaking.

This affinity for prototyping and exposure to a wide range of materials was clearly to serve him well in the future, and he dryly observes that his current planemaking workshop “is effectively equipped as a prototype shop.”

The Start of Planemaking

Norris reproductions. Shown here are Holtey’s versions of the Norris A27 Bullnose and A28 Chariot planes

It is no surprise that the original Norris infill planes were what originally fired Holtey’s imagination for planemaking. Having been captivated by pictures of the Norris planes, Holtey met Alan Beardmore of infill manufacturers Henley Optical, and Bill Carter (the grandfather of modern British infill planemaking) with whom he started attending David Stanley Auctions to obtain working specimens of original Norris planes.

Holtey’s first planes were built on a modelling lathe and secondhand milling machine in an 8′ x 15′ shed. Those early planes rigidly followed the original Norris designs, scaled up from catalog pictures (this was before the Internet made details of classic planes readily available); he focused on reproductions of the Norris A1 panel plane and A7 shoulder plane, followed by the A28 chariot and A31 thumb planes.

“I’ve always had a fascination with engineering, even though I’m not an engineer. I used to feel embarrassed about what I did – I felt like I was a fraud,” says Holtey. “Because I knew what I wanted but I had to move into another world. I knew what I wanted to do but didn’t know how to go about it. So I worked in secret so that I could do what I wanted without feeling any pressure.”

Steps Toward Innovation

The original masterpiece. The Holtey 98 Smoothing Plane was the maker’s first original design.

His satisfaction in making pure reproductions was short-lived, so Holtey started to design improvements that addressed what he perceived as deficiencies in the original Norris planes.

The first Holtey original design was the 98 smoothing plane, named after the Exempla 98 fair in Munich, for which he originally designed the tool. Now considered a classic design, the 98 was for Schwarz “a total revelation,” and represents the unveiling of a number of quintessential Holtey design features, including a stainless steel body joined through integral rivets rather than dovetails, bevel-up blade orientation and a rear tote fitted to the plane body with hidden fixtures.

For planemaker Konrad Sauer, of Sauer & Steiner Toolworks, the 98 represents Holtey’s “most significant contribution to modern planemaking” specifically thanks to these innovative design choices. That the 98 no longer appears to be revolutionary is testament to the quality of Holtey’s designs. “It does not stand out because so many of its features and thinking are [now] in everyone else’s work,” says Sauer.

Better bun. The Holtey A13 features an improved front bun design over the original Norris plane.

Similarly, nearly all modern reproductions of the Norris A13 made since Holtey’s A13 plane have adopted Holtey’s improved front bun in preference to the original design.

The front bun on Holtey’s version is “a fantastic piece of design and has been so successful that very few people realize it’s not original to a Norris,” says Daed Toolworks planemaker Raney Nelson.

“Many newer makers copy [Holtey’s] work thinking they are copying ‘original patterns,’” says Sauer.

For Schwarz, the redesign of the A13 is emblematic of Holtey’s work. While the “original A13 has an ugly front bun, Karl’s redesign of it is so perfect that many people now think that’s how Norris made them as well,” says Schwarz.

Design Process

Holtey comes across as something of a contradiction. Given his reputation for a precision that borders on the obsessive, it is disarming when he explains that his approach to planemaking is based on what he says are hunches. “Some people work things out with mathematics. I work things out with guesswork and gut feeling,” he says.

Holtey explains that his designs come from making small but significant improvements to pre-existing designs. In this respect he sees himself as improving the wheel, but not reinventing it. “Everyone has a picture in their mind of what a ‘plane’ is and looks like,” he says. He characterizes his work as innovations to address perceived failings in the functionality of existing planes, rather than changes for the sake of innovation itself.

Remarkably, given the amount of time and effort Holtey expends on every detail of his planes, he suggests that his focus is “to keep things simple and functional.”

Modern material. Holtey’s use of modern acrylics is distinctive. Here are two totes for the 984 panel plane.

“He was the first planemaker in several generations who put the functionality of the tools back to the absolute forefront,” in an industry that had previously focused on producing infill planes “based on their appearance, and their relationship to the historical record much more than for their abilities as working tools,” says Nelson.

Once the outline design has been fleshed out, Holtey undertakes a weight-relieving exercise to remove as much mass as possible without affecting the mechanical properties of the plane. It is this critical design process, together with Holtey’s strong art deco aesthetic, which resulted in the low profile of the 984 panel plane and the distinctive curves of the 983 block plane.

Similarly, Holtey’s innovative use of materials, including stainless steel for plane bodies and acrylic for totes, is driven by frustration with what he considers to be the shortcomings of traditional materials. So his decision to abandon the infill pattern planes for which he was known in favor of all-metal designs was prompted by what he perceives as the incompatibility between high-precision engineering and the seasonal movement of wooden wedges and infills.

Final design. The 984 panel plane will be Holtey’s final design for a production run before retiring.

Despite enjoying some success in mitigating seasonal wood movement Holtey ultimately observes that, “the dimensional stability of wood has always been the bane of my life.” But he explains that even when devising innovative solutions, he tries not to lose sight of tradition, and maintains that Norris and the other classic infill manufacturers would be using stainless steel and acrylics if they were manufacturing today.

Holtey’s approach to refining pre-existing designs does not stop with infills. A key feature of his 983 block plane was developed to address the tendency in this style of plane for the blade-clamping mechanism to fall out of alignment when under pressure, resulting in a loss of clamping force. To address this flaw, the 983 has a curved mating surfaces between the blade-clamping wheel and the clamping shoe, which ensures that the assembly is held in alignment and full clamping pressure is transferred to the blade.

This attention to detail has resulted in what Schwarz suggests is Holtey’s enduring legacy. “Whether other makers admit it or not, Karl has had an enormous impact on the world of tool making. He set the bar higher than it has ever been set for fit and finish. He changed people’s view of the tolerances that are allowable in making tools – for better or worse,” says Schwarz.

The Message

Under pressure. The blade-clamping mechanism of the 983 may not look unusual, but it addresses some common design flaws through meticulous attention to detail.

In person Holtey comes across as fiercely stubborn and opinionated, a generous host who is eager to learn what others think of his work, and utterly committed to building to an intimidating degree of precision. He swiftly dismisses the need for tight plane mouths, although he offers planes with wafer thin mouths because that is what customers expect, and is equally dismissive of the need for chipbreakers.

He is also keen to emphasise “the message” behind Holtey Classic Hand Planes, even if that message is not easily expressed.

“It’s an attitude, but it’s hard to explain. The closest analogy is city people who are happy to get the milk off their doorstep without knowing the effort that went into producing that milk – what was involved,” he says. “My message is the effort that is involved in each of my planes – making things as precisely as I can. My planes are expensive, but I still make a loss on each one. And I respect that people are willing to pay so much money for one of my planes.”

Holtey needn’t worry that his message is being lost; all of the other planemakers I interviewed for this piece remarked on how Holtey’s pursuit of perfection had influenced their own work.

“I soon realized that everyone else was making a Timex, while Karl was making a Rolex,” says Anderson.

What Follows Planemaking?

And so it is that after more than 26 years of planemaking, Holtey is retiring; the 984 panel plane will be his final run. He says that the decision to retire was prompted by the realization that the 983 was the pinnacle of everything he’s worked toward. “With each plane I want to make it better than the one that preceded it,” he says, and the 983 leaves little for him to strive for.

And what of Holtey’s plans for retirement? There is, it seems, no risk of his slowing down any time soon. He will return to a number of orphaned plane projects – curiosities that fell by the wayside as he focused on his core range. Among these is a plane he refers to as the “Push Me, Pull You” – Holtey’s take on the concept of a variable pitch plane, which he promises will allow the user to switch between two popular pitches without needing to disassemble the tool.

At present, Holtey’s intention for these orphans is to build only a few of each plane, almost as proofs of concept rather than a full production run. During the time I spent at his workshop, Holtey expressed no intention in selling these, so it appears the most Holtey aficionados can hope for at this point is some scintillating glimpses on his blog.

Taking aim. Holtey already has the metalwork done for a medieval-inspired crossbow.

A keen target shooter, Holtey also intends to spend his retirement experimenting with making his own ammunition, and possibly his own rifles. There is also the small matter of a medieval crossbow design, for which he has fabricated the metal parts; all that remains is to work on the wooden elements. If ever completed, I know at least one woodworker who would find the prospect of a crossbow built to Holtey’s usual levels of precision to be very tempting indeed.

Even as Holtey plans his retirement, it is certain that his influence will continue to be felt. As Nelson observes, many of Karl’s innovations have “been so effective that it now looks crazy to approach the tools in any other way.” Schwarz agrees. “Even though Karl is retiring from planemaking, his tools and the ideas behind them will echo in this craft for many generations.” PWM

Kieran is a luthier and woodwork writer. Read his blog at overthewireless.com.

From the June 2016 issue

Editor’s note: For more – much more – on handplanes, check out the wide selection of videos and books on the topic at our online store.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.