We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Understand the fundamentals.

A wood finish is a clear, transparent coating applied to wood to protect it from moisture and to make it look richer and deeper. This differs from paint, which is a wood finish loaded with enough pigment to hide the wood. And it differs from a stain, which is a wood finish and a colorant (pigment or dye) with a lot of thinner added so the excess stain is easy to wipe off. The remainder just colors the wood; it doesn’t hide the wood.

Unfortunately, the term “finish” also refers to the entire built-up coating, which could consist of stain, several coats of finish (a “coat” is one application layer) and maybe some coloring steps – for example, glazing or toning – in between these coats. For some reason, we have only one word to refer to both the clear coating used, and to all the steps used.

Usually, the context makes clear to which is being referred.

Purpose of a Finish

A finish serves two purposes: protection and decoration.

Protection means resistance to moisture penetration. In all cases, the thicker the finish, the more moisture-resistant it is. Three coats are more protective than two, for example. Boiled linseed oil, 100 percent tung oil and wax will dry soft and gummy, however, so all the excess has to be wiped off after each application to achieve a functional surface. Therefore, no significant thickness can be achieved. Protection is limited with these finishes.

Finishes decorate by making wood look richer and deeper. The impact is less dramatic on unstained lighter woods such as maple and birch, and greater on stained and darker woods such as cherry and walnut.

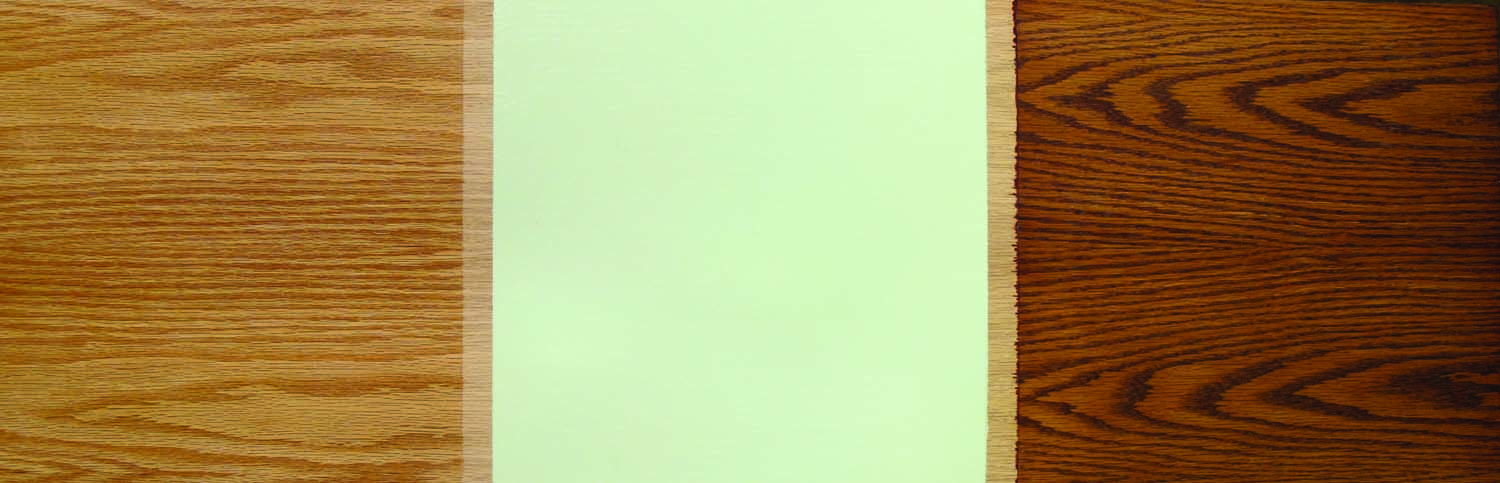

Polyurethanes. The left section of this panel was finished with water-based polyurethane, which, like all water-based finishes, adds little color to the wood. The finish just makes the wood a little darker (compared to the lighter strip down the middle, which was covered with tape). The right section was finished with oil-based polyurethane, which, like most finishes except water-based finishes, adds some degree of yellow/orange coloring to the wood. Oil-based polyurethane continues to darken as it ages, while water-based polyurethane doesn’t darken.

Types of Wood Finish

Common categories of wood finish include the following:

- Oil (boiled linseed oil, 100 percent tung oil and blends of these oils and varnish).

- Oil-based varnish (including alkyd, polyurethane, spar, wiping and gel varnish).

- Water-based finish (a finish that thins and cleans up with water).

- Shellac (an ancient finish derived from resin secretions of the lac bug).

- Lacquer (the finish used on almost all mass-manufactured household furniture made since the 1920s).

- A large number of two-part, high-performance finishes used in industry and by many professional cabinet shops.

Wiping varnish is alkyd or polyurethane varnish thinned about half with mineral spirits so it’s easy to wipe on and wipe off. You can make your own, or there are a large number of brands, which, unfortunately, are poorly labeled. (read more on wiping varnish here)

The primary differences in the finishes are as follows:

Finish on oak. On this oak panel, a clear finish was applied to the left section, paint to the middle section and a stain and clear finish to the right section.

■ Scratch, solvent and heat resistance. Oil-based varnishes and high-performance finishes provide the best scratch, solvent and heat resistance. Water-based finishes are next. Shellac and lacquer are susceptible to all three types of damage. Oil is too thin to be effective.

■ Color. Water-based finishes add little color to the wood. All other finishes (except possibly CAB-Acrylic) add some degree of yellow-to-orange coloring.

■ Drying time. Shellac, lacquer and high-performance finishes dry the fastest. Water-based finishes are next. Varnish and oil require overnight drying in a warm room.

■ Solvent safety. Boiled linseed oil and 100 percent tung oil are the least toxic finishes to breathe during application because they don’t contain solvent. Water-based finishes (thinned with water and a little solvent) and shellac (thinned with denatured alcohol) are next. Oil-based varnish thins with mineral spirits (paint thinner), which some people find objectionable but which isn’t especially toxic. Lacquer and high-performance finishes thin with solvents that are the most hazardous to be around.

Sealing Wood

The first coat of any finish seals the wood – that is, stops up the pores in the wood so the next coat of finish (or other liquids) doesn’t penetrate easily. This first coat raises the grain of the wood, making it feel rough. You should sand this first coat (with just your hand backing the sandpaper) to make it feel smooth. You don’t need a special product for this first coat unless you have one of two problems you want to overcome.

■ Alkyd varnish and lacquer can gum up sandpaper when sanded, so manufacturers of each provide a special product called “sanding sealer” with dry lubricants added to make sanding easier and speed your work. Sanding sealers weaken the finish, however, so you should use them only when you’re finishing a large project or doing production work.

■ Sometimes, there are problems in the wood that have to be blocked off with a special sealer so they don’t telegraph through all the coats. These problems are resinous knots in softwoods such as pine, silicone oil from furniture polishes that causes the finish to bunch up into ridges or hollow out into craters, and smoke and animal-urine odors. The finish that blocks these problems (“seals them in”) is shellac, and it should be used for the first coat. Notice that, except for resinous knots, the problems are associated with refinishing.

Sheen

Sheen. A finish can have an infinite number of sheens depending on how much flatting agent is added.

Oil-based varnishes, water-based finishes and lacquers are available in a variety of sheens, ranging from gloss to flat. All sheens other than gloss are created by the solid-particle “flatting agents” manufacturers add to the finish. The more flatting agent added, the flatter the sheen. These flatting particles settle to the bottom of the can, so you have to stir them into suspension before each use.

You can get any sheen you want by pouring off some of the gloss from a can in which the flatting agent has settled (don’t let the store clerk shake the can) and blending the two parts. Or you can mix cans of gloss and satin to get something in between. You will need to apply the finish to see the sheen you’ll get. It’s the last coat you apply that determines the sheen (there is no cumulative effect), so you can experiment with each coat.

Finish Application

Oil, wax, wiping varnish and gel varnish can be applied with a cloth or brush, then wiped off. The other finishes are usually applied with a brush or spray gun.

Brushing is simple – essentially no different than brushing paint. Spraying is also simple, but spray-gun care and tuning is more complicated, and spray guns and their sources of air (compressor or turbine) are considerably more expensive than brushes.

Application Problems

Common problems and ways to avoid them:

■ Brush marks and orange peel. Eliminate these by thinning the finish 10 percent to 30 percent so it levels better.

■ Runs and sags. Watch what is happening in a reflected light and brush out the runs and sags as they occur.

■ Dust nibs. Keep your tools, the finish and the air in the room as clean as possible.

■ Bubbles. Brush back over to pop the bubbles, or thin the finish 10 percent to 30 percent so the bubbles have more time to pop out.

No matter what the problem, you can always fix it by sanding the finish level and applying another coat.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.