We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Deck boards cup. It’s common to see randomly laid deck boards all cupped after months of exposure to rain. The warping isn’t the result of how the boards were laid – heartwood side up or down. It’s the result of compression shrinkage caused by the continual wetting and drying out of just the topside.

Once an inaccuracy gets started, it becomes almost impossible to correct.

“A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on,” said Winston Churchill (or others, if you believe different attributes).

If you are familiar with my teaching and writing about finishing, you know that I have devoted a lot of effort to making sense of the products we use in finishing, especially the ones that don’t seem to match what the label says they are.

The word “lie” in Churchill’s quote is pretty strong. It implies intent, and in many cases I don’t believe that manufacturers of finishing products and people writing or teaching about finishing intend to say or write something that isn’t true. They just don’t understand the products they’re selling or writing about.

With that said, it bothers me a lot when I see some of the inaccuracies still being repeated in magazines nearly three decades after I first began calling attention to them.

Oil & Wiping-Varnish Finishes

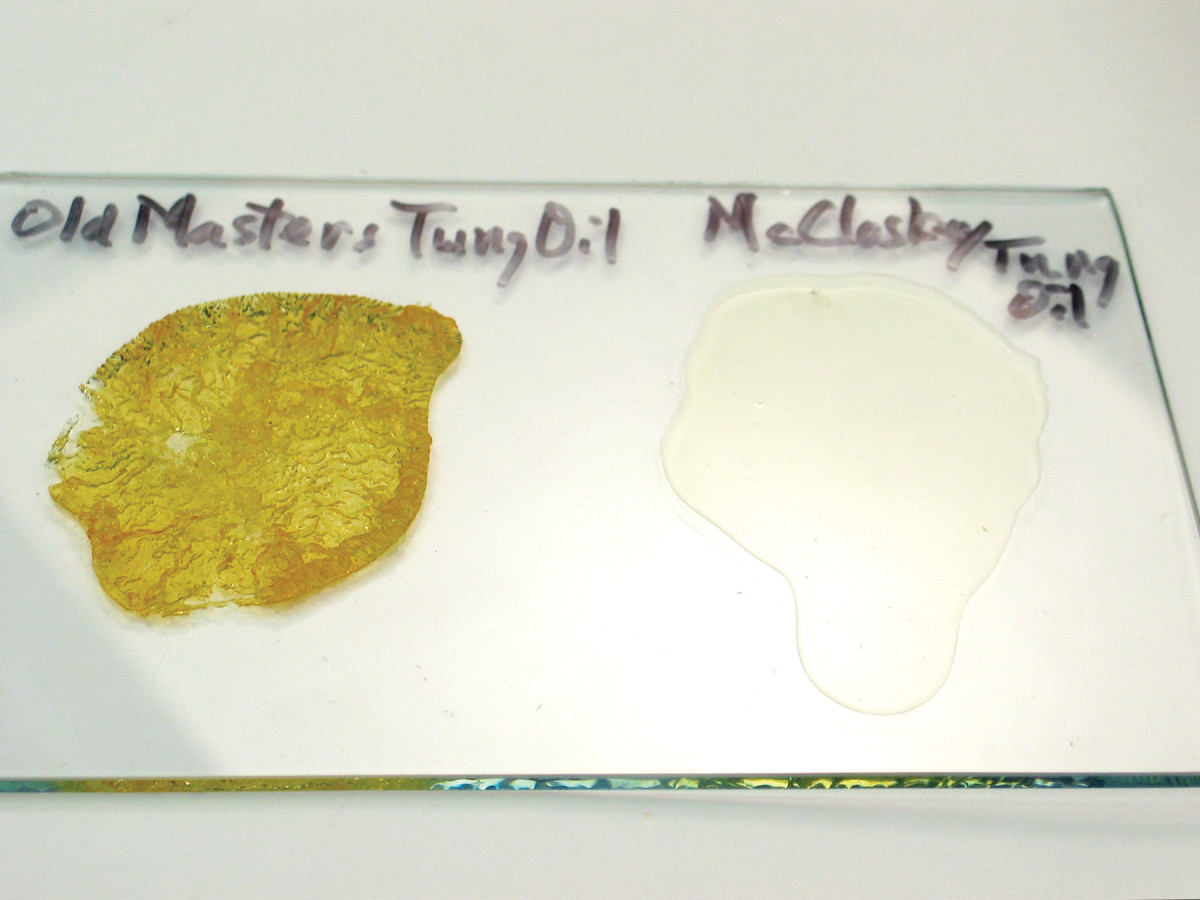

Oil and wiping varnish. When I buy a container of wipe-on finish I typically put a puddle on the top and let it dry so I can determine whether it’s oil or wiping varnish. Oil, or any finish that contains oil, such as Danish oil, wrinkles and stays soft. Wiping varnish dries smooth and hard.

Ever since I began woodworking in the 1970s, there has been confusion about “oil” finishes. The confusion exists because some manufacturers label their wiping-varnish finishes “oil.” The confusion is then compounded when articles in woodworking magazines repeat the manufacturer’s labeling even though in many cases the labeling doesn’t make sense. The products labeled oil just don’t act like oil.

In fact, oil and wiping-varnish finishes, no matter how they are labeled, could hardly be more different. Linseed oil and tung oil, the two drying oils commonly available to us, never get hard so they can’t be built up. All the excess has to be wiped off after each coat or the surface remains gummy and sticky.

In contrast, wiping-varnish finishes are varnish (sometimes polyurethane varnish) thinned enough with mineral spirits so they are easy to wipe on the wood. As with all varnishes, they harden well overnight so they can be built up to a very protective and durable film. There’s no need to wipe off the excess after each coat.

The first problem I came across in a magazine article was General Finish’s Arm-R-Seal being identified as oil. It’s not, and neither is Seal-A-Cell. Both are wiping varnishes. (So you may question why you’re instructed to apply both.) The fault for any confusion begins with the manufacturer, of course, and how it promotes these products. But we should know better by now.

Tung Oil

Tung oil. The problem with tung oil is that manufacturers often label wiping varnish “tung oil” as McCloskey has done here on the right in contrast to Old Masters on the left. You can tell what the finish is by letting a puddle dry on a non-porous surface or by whether on not a thinner is listed on the can. Wiping varnish always contains a thinner, tung oil doesn’t.

The oil most shrouded in mythology is tung oil. Like linseed oil, tung oil is a vegetable oil that doesn’t harden well. So all the excess has to be wiped off after each coat to get a functional finish.

Beginning in the late 1960s a fellow named Homer Formby began promoting a wiping-varnish finish he labeled “Tung Oil Finish” in TV infomercials and in appearances at antique clubs and stores. He claimed that tung oil, which originates in China, is such a great finish that it was used to protect the Great Wall of China! Come on! The Great Wall of China is made of stone and in its many parts is over 13,000 miles long and high enough to keep marauding tribes out. You have surely seen pictures of tourists walking on parts of it near Beijing. It’s so huge that it can be seen from space.

The idea of people coating this stone structure with oil to protect it is absurd. And the further idea that the oil would hold up for longer than a few months when exposed to the harsh weather in northern China makes this claim even more absurd. So imagine my surprise and exasperation when I read this totally unbelievable claim repeated recently.

Sanding

Cupped warp. Old furniture was rarely finished on the underside of the top so one would expect it to bow when adjusting to the dryer conditions in modern buildings as the finish on the top slowed the drying out. The opposite happens, however, which indicates that finishing the underside doesn’t improve the stability of the wood.

The same article suggests bringing out more clarity in wood by sanding it to 800- or 1000-grit. This is true if you don’t apply a finish. But as long as sanding scratches don’t show, you won’t see any difference in finished wood by sanding to very fine grits.

George Frank, if you remember him, used to get a kick out of passing around a maple board in classes he taught that he had sanded to 2000 grit and asking if anyone could identify the finish. The board was shiny and did look finished, so everyone had a guess. But it was a trick. It hadn’t been finished at all, just sanded.

There are three problems with sanding to very fine grits. First, it’s a lot of work. Second, it does no good. If you were to leave the wood unfinished, it would soon lose its shine as humidity raises the grain. And third, there’s no resistance to liquids and stains.

Finishing Both Sides

Formby started it. Homer Formby started labeling his wiping varnish “tung oil” in the late 1960s and promoted it widely. Other manufacturers then began following Formby, but many didn’t seem sure what Formby was selling so some packaged wiping varnish and others packaged real tung oil. So the confusion started.

And finally, here’s another inaccuracy that got started in the 1970s and refuses to die – that you should finish bottoms and insides to provide equilibrium and prevent warping. Finishing bottoms and insides does make them look and feel better, though, so you may choose to do it. But don’t kid yourself about adding stability.

Here’s the proof. Look at any old tabletop that has been finished only on the topside (which was standard in factories before the 1920s) and has warped. The top will be cupped, not bowed, as you would expect in the drier conditions in modern buildings. In other words the finished topside should slow the drying and shrinking of that side more than the unfinished bottom side, so the top would bow. But it cups.

The true cause of warping, other than for wood that hasn’t been dried properly, is the topside or exposed side being wetted and dried out over and over causing “compression shrinkage.” The wood cells try to swell but can’t due to the wood’s thickness. So they compress to oval shapes and don’t resume their previous cylindrical shapes when they dry out. You can see the cupping clearly on exposed decks which go through the wet/dry cycle countless times.

On tabletops that are frequently wiped with a damp cloth, it’s necessary to keep the finish in good shape to prevent moisture from getting to the wood. This is the way to prevent warping.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.