We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Spraying. There’s nothing special about spraying catalyzed finishes; they spray similarly to nitrocellulose lacquer.

Apply a professional, quick-drying and durable finish at home.

You may have heard of catalyzed finishes: pre-catalyzed lacquer, post-catalyzed lacquer and catalyzed or “conversion” varnish. These finishes are commonly used in industry and in cabinet and professional refinishing shops. But there’s no reason you can’t use them also.

The primary advantages of catalyzed finishes are their durability, which is similar to oil-based polyurethane, and their fast drying, which is similar to nitrocellulose lacquer. The fast drying significantly reduces dust nibs on horizontal surfaces, and runs and sags on vertical surfaces, and it makes possible the application of all coats in a single day.

The disadvantages are the more irritating solvents and acid catalysts used (so you need a good exhaust system and maybe an organic-vapor respirator mask), the fast drying that makes application with a spray gun almost essential, and the availability only in gallon-or-larger sizes. Also, compared to lacquer, shellac and water-based finish, catalyzed finishes are much more difficult to repair invisibly if they should get damaged.

Catalyzed finishes are usually available at paint stores and distributors that cater to the professional trades. I’ve never seen these finishes at home centers.

The Ingredients

The distinguishing feature of catalyzed finishes, and the ingredient that gives them their name, is the acid catalyst that is added to make them cure. All solvent-based finishes referred to as catalyzed finishes employ the aid of an acid in the curing process.

In addition to the acid, these finishes contain an alkyd resin and one or both of the amino resins: melamine formaldehyde and urea formaldehyde. Most also contain nitrocellulose lacquer.

The alkyd and amino resins are crucial to these finishes. You can’t turn nitrocellulose lacquer into a catalyzed finish simply by adding an acid catalyst to it.

Defining the Types

There are three large categories of catalyzed finish: catalyzed (“conversion”) varnish, post-catalyzed lacquer and pre-catalyzed lacquer.

When the acid catalyst is packaged separately from the finish and no nitrocellulose is included, the finish is commonly called catalyzed or conversion varnish. Because this finish cures entirely by the crosslinking that occurs between the alkyd and amino resins, it is the most durable of the catalyzed finishes. But without the nitrocellulose, the finish dries slower and is more finicky.

When the acid catalyst is packaged separately from the finish and nitrocellulose has been added, the finish is commonly called post-catalyzed lacquer. The added nitrocellulose makes this finish a little easier to use because it hardens faster and bonds better between coats and over stains and glazes. The nitrocellulose also makes the finish a little easier to repair, but it weakens the finish slightly against wear, water, heat, solvents, acids and alkalies.

You can distinguish between these two finishes by the thinner used. Catalyzed varnish thins with toluene (toluol), xylene (xylol) or a similar proprietary manufacturer’s solvent; post-catalyzed lacquer thins with lacquer thinner.

When a weaker acid catalyst is included in the finish along with nitrocellulose, the finish is commonly called pre-catalyzed lacquer (or “pre-cat”). It’s the easiest of the catalyzed finishes to use (very similar to using nitrocellulose lacquer itself), but it’s also the least durable of these finishes. Nevertheless, it’s still as durable as oil-based polyurethane varnish, so it’s durable enough for most situations.

All catalyzed finishes are available in various sheens including gloss, satin and flat.

If you are considering trying a catalyzed finish, I recommend beginning with pre-catalyzed lacquer, which is ready to use right out of the can.

Adding a Catalyst

Adding catalyst. To initiate the crosslinking of the amino and alkyd resins, you have to add the acid catalyst to catalyzed (“conversion”) varnish and post-catalyzed lacquer before beginning to spray.

With post-catalyzed lacquer and catalyzed varnish, you have to add the catalyst yourself (unless you find a distributor who will do it for you), and you have to follow the manufacturer’s directions exactly. These directions differ among brands.

If you add too little catalyst, the finish won’t harden properly. If you add too much, the finish may develop a haze or “acid bloom,” which will continue reappearing even after you wipe it off.

Because the curing begins immediately after the catalyst is added, you have a limited time to get the finish applied or it will harden in your spray gun, possibly ruining it. This is called the finish’s “pot life.” It varies from several hours to several days, depending on the brand.

Moreover, there are often specific rules for applying each coat, and a window for getting all the coats applied to avoid bonding or wrinkling problems.

Catalyzed Finish Problems

Cracking & peeling. Catalyzed (“conversion”) varnish is the most finicky of the catalyzed finishes, partly because of the difficulty getting a good bond over stains, glazes, other finishes and even over itself. In this instance, the catalyzed varnish was applied over old nitrocellulose lacquer and began cracking and peeling soon after.

Pre-cat is very forgiving, similar to nitrocellulose lacquer. But post-catalyzed lacquer and, especially, catalyzed varnish are less so. You need to be familiar with the common problems so you can avoid them.

The most unique is excessive film build. These finishes get so hard that they crack if the film build is too thick. This cracking may not show up for months. Most manufacturers caution you to keep the total film build under five mils (five-thousandth of an inch), which is about three coats.

All finishes are sensitive to temperature during drying, but catalyzed finishes are more so than most. The temperature during application and for up to six hours afterward should be kept above 65° (70° is better) or the finish might not cure properly.

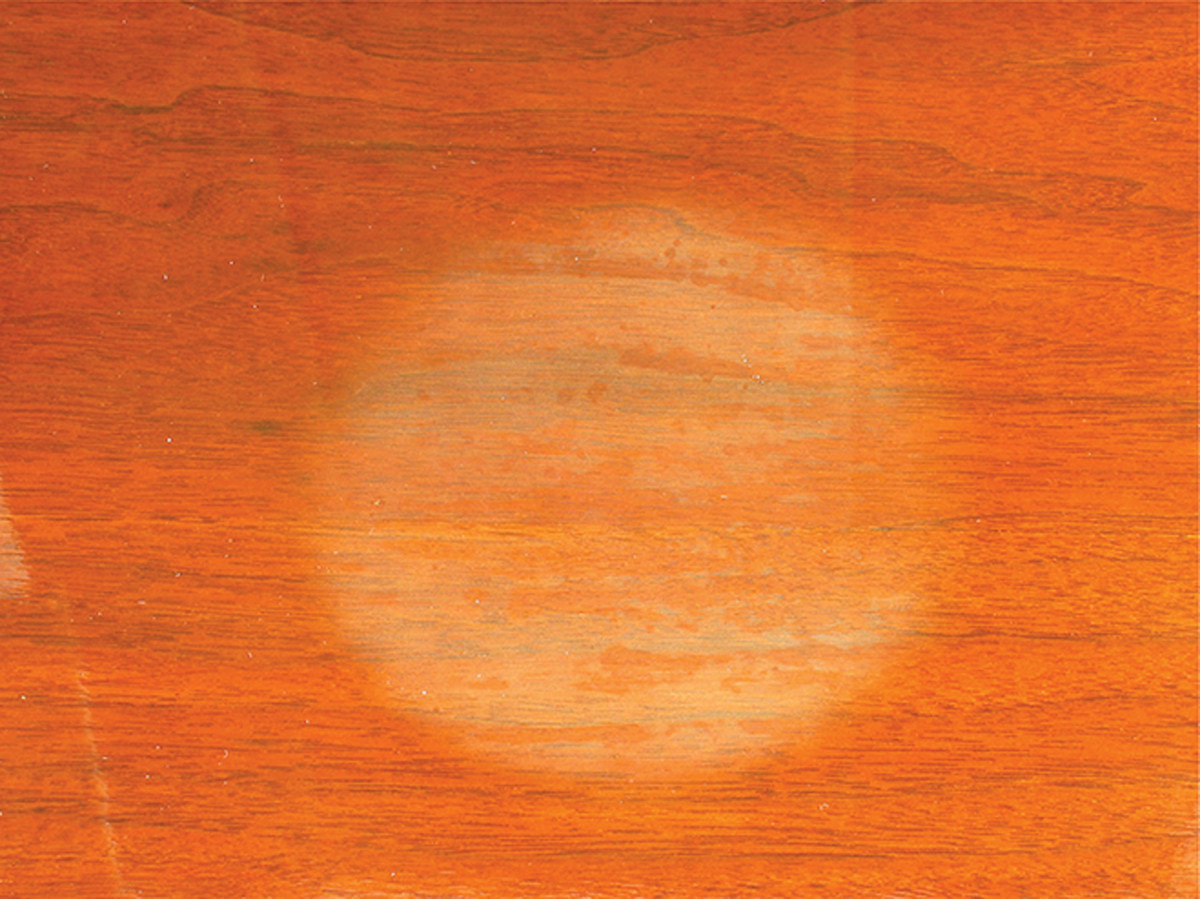

Durable, but…. Catalyzed (“conversion”) varnish is the most durable of the catalyzed finishes. But after it has aged a number of years, it can still be damaged. When this happens, the damage is often very difficult or impossible to repair. In this case, a 30-year-old finish was damaged by a hot pizza. Spraying a slow solvent or abrading, which are both effective on nitrocellulose lacquer, had no impact. The table had to be refinished.

Because of their high solids, catalyzed finishes often don’t bond well to wood that has been sanded to too fine a grit, especially to tight-grained woods such as maple and birch. The best practice is to sand no finer than #-220 grit just before applying the finish.

Alternatively, for the first coat you can use a stearate-free “vinyl” sealer, which is water resistant and should be available from the same suppliers. (Catalyzed finishes don’t bond well to sanding or vinyl sealers that contain stearates.)

Bonding to stains, glazes and pore fillers can be a problem, especially with catalyzed varnish. To ensure good results, perform the decorative steps within washcoats (highly thinned coats) of vinyl sealer, then apply the topcoats of conversion varnish.

Above all, when using a catalyzed finish with the acid catalyst supplied separately, follow the directions of the manufacturer.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.