We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

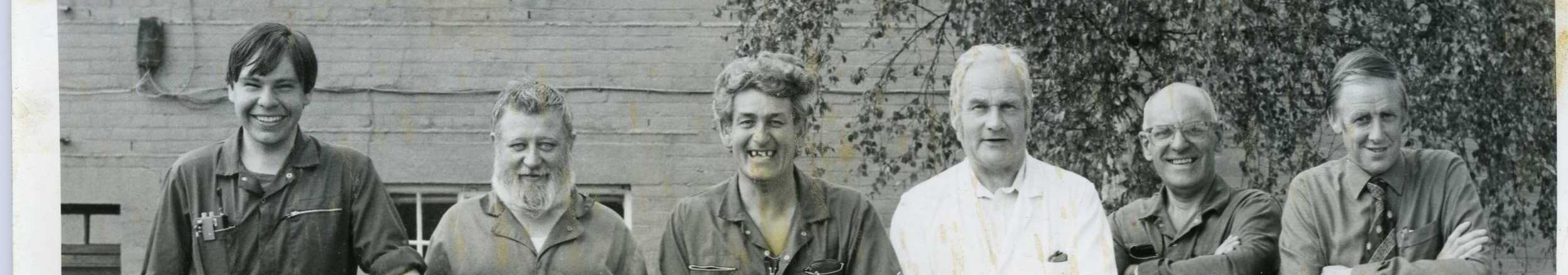

My colleagues during my brief employment at the Duxford Airbase branch of the Imperial War Museum, 1986

During an interview last summer, Laura Mays asked how I would divide up furniture makers into different types. It was a provocative question, not least for someone who has witnessed lots of change in the field over the past 40 years.

I started by invoking the primary distinction from my early years–initially as a student, and then in my first couple of jobs: amateur and professional. This was the only differentiation I remember being made at the time.

In rural England during the early 1980s, it was a perfectly good distinction, although the terms “amateur” and “professional” are (and were, at the time) freighted with unfortunate connotations. While doing a “professional” job is generally understood to imply high standards, some of those who build only in their spare time (“amateurs”) have more refined skills and are even more meticulous in their work. Counter-intuitive though this may be, it makes sense. Those who don’t depend on building Windsor chairs or period-perfect reproduction highboys to pay their mortgage, health insurance premiums, and everything else we typically expect a job to provide have the luxury of lavishing as much time, ingenuity, and perfectionism on a piece as they please.

In our contemporary era, with its so-called gig economy, this distinction between amateur and professional has more porous boundaries. Let me set up the contrast this way: The overwhelming majority of furniture makers I knew 40 years ago worked a basic 45-hour week in shops owned by someone else. Making furniture and built-ins (every professional I knew back then worked in a shop that made built-in cabinetry in addition to freestanding furniture, because doing so was necessary to make ends meet) was a job. Many of us may have loved the work (in the much-qualified, mature sense of love), but it was still A Job. We went to work and did our best, and many of us were paid quite modestly, which we understood to be appropriate for the kind of work we were doing–i.e., building practical furnishings to be used by regular people in their homes.

Those were the days before social media introduced the notion that Anyone Can (or perhaps even deserves to) Be An Instagram/YouTube Woodworking Rockstar.

***

Today there seem to be fewer jobs available for those wishing to build furniture and cabinetry in the kinds of small shops where I started my woodworking career. Some reasons I’m aware of are the following:

- Everyone’s a furniture maker. Not only has working with your hands become downright fashionable (in contrast to being seen, rightly or wrongly, as evidence that academics are not your strength), prompting interest in furniture making among tens of thousands who might otherwise have stuck to gardening or golf in their spare time; the widespread availability of lower-cost imported tools and machinery combined with instruction in the form of short courses at schools and free (or low-cost) online content has also significantly increased competition.* When potential customers can have their kitchen island built by the neighbor down the road who builds furniture in his spare time with lower business-related costs and the greater economic flexibility afforded by income from a day job, it may not be wise for the owner of a cabinetmaking shop to try to keep 12 skilled craftspeople steadily employed.

- Many people (at least, over the age of 45) just don’t want to risk employing others** any longer, because they had to lay good people off in the last recession. This may not be noticeable during our current bullish economy, but come a recession, the dollars or pounds in circulation are prone to dry up in a flash (except among the wealthiest clientele). Laying people off is one of the worst kinds of pain. And employing people is a job in its own right.

- In the United States and United Kingdom, government regulations that apply to employers and employees have become considerably more stringent over the past few decades. I won’t go into detail here, other than to acknowledge that employing people today is more costly than it used to be.

I’m sure I could add to this list (and readers, please feel free to do so in the comments), but for now I hope I’ve made my basic point: The distinction between amateur and professional is far harder to make today than it was when I first started woodworking.

Next up: Studio versus Shop.

*I know, it’s unfashionable to talk about competition instead of proclaiming the gospel of abundance, but this is my post, based on my life experience.

**The powers that be define “employing others” strictly. If you have an unpaid “intern,” or even someone whom you pay on a casual basis, you owe it to yourself (and to him/her/them) to bone up on employment law. Invaluable assistance in such matters is available through local offices of the Small Business Administration and SCORE.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Waiting for Part 4; different types of social media woodworkers? Basic YouTubers, Instagram Rockstars (your term), bloggers (and abandeond bloggers), lumber jock guy, creekers, facebook groupies, content creators, maker meet up person, influencers, pod cast dudes, IGTV instructors, Etsy sellers…. phew! Have I missed any body?

You’ve got it, at least for part 3. But first we have part 2, which I’m relieved to see you haven’t addressed here. I’m planning to post that one a week from Monday, when I will be driving to Asheville.