We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

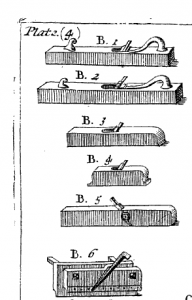

Plane detail from Plate 4 of “Mechanick Exercises.” B1: Fore-plane; B2: Jointer; B3: Strike-block (small jointer/miter plane); B4: Smoothing-plane; B5: Rabbet Plane; B6: Plow

When you have occaſion to take your Iron out of the Stock to rub it, that is, to whet it, you may knock pretty ſmart Blows upon the Stock, between the Mouth and the Fore-end, to looſen the Wedge, and conſequently the Iron,

Theſe ways of setting are uſed to all other Planes, as well as Fore-planes.

In the uſing of this, and indeed, all other Planes, you must begin at the hinder end of the Stuff, the Grain of the Wood lying along the length of the Bench, and Plane forward, till you come to the fore-end, unleſs the Stuff proved Croſs-grain’d, in any part of its length ; for then you muſt turn your Stuff to Plane it the contrary way, ſo far as it runs Croſs-grain’d, and in Planeing, you muſt, at once, lean pretty hard upon the Plane and alſo thruſt it very hard forwards, not letting the Plane totter to, or from you-wards, till you have made a Stroak the whole length of the Stuff. And this ſometimes, if your Stuff be long, will require your making two or three ſteps forwards, e er you come to the fore-end of the Stuff : But if it do, you muſt come back, and begin again at the farther end, by the ſide of the laſt plan’d Stroak, and ſo continue your ſeveral lays of Planeing, till the whole upſide of the Stuff be planed.

— Joseph Moxon

Over the weekend, I spent several hours on a close read of the joinery sections of a facsimile version of Joseph Moxon’s “Mechanick Exercises or Doctrine of handy-works” (the 1703 edition). What I learned is that there really isn’t anything new in woodworking (although some terminology, and our ways of talking about the craft, have changed).

Most of all, though, it got me to thinking about for whom this book was written.

Without going much into my dissertation research (which investigates a similar question in relation to the plays and “courtesy titles” of the late 16th and early 17th centuries), it stands to reason that those actually involved in the joinery craft (or the other “mechanicks” about which Moxon wrote, for that matter) weren’t learning about it through reading; they were learning by doing.

The Statue of Artificers (1563) stipulated that an apprenticeship – a 7-year indenture to a Master – was legally required to enter a trade, in which time the apprentice would the taught the “arts and mysteries” of the craft (1). That law remained in force until 1814 (though clearly many of its points were routinely flouted, and the guilds began to lose power to enforce these rules from the late 17th-century on). Boys entering into an apprenticeship in the craft likely averaged 14 years of age. Boys of that age were not (likely) reading Joseph Moxon – assuming they could read at all.

In England in 1700, the literacy rate among men was 35-40 percent (2), and a table of goods (3) owned by those in various occupations show that less than 10 percent of carpenters owned books. (Carpentry is, of course, not the same as joinery, but I think it’s safe to assume a corollary – though carpentry was considered the less-skilled trade of the two).

So who was buying and reading this serial publication when it was first published in the 1660s? And who was buying it in 1703 when it became available as a complete book?

I don’t know – but I’m curious. I could speculate ad nauseum based on my dissertation research…but that would be a massive distraction from what I’m supposed to be doing in my off time. Once I get done with that pesky 250+-page paper on Shakespeare et al. (4), perhaps I’ll set my sights forward by 75-100 years (beyond an intervening regicide, revolution and restoration) and dig further into it.

And if nothing else, I learned how to render in html a long s – for your reading annoyance.

• Get your copy of Moxon here.

(1) Yes, I realize that’s a gross oversimplification.

(2) Sources vary greatly here; stating statistics from 28 percent – 60 percent across all strata of society

(3) Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain 1660-1760. (New York: Routledge, 1988.)

(4) For those of you who’ve kindly asked, yes, I’m still planning to finish it.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Do we know how much it cost and what the general wage level was?

I’m sure there would have been a section of society that had to make for themselves or go without. I don’t know if that class could afford Moxon … or if they would get their (potentially limited) info from friends and family.

HOW DO I GET MOXON? The Link doesn’t work.

Very Interesting. My best wishes for your success. This causes me to wonder…. If Moxon wrote for the more educated reader while the craftsmen were more or less illiterate, have you ever researched to see what percentage of Popular Woodworking subscribers actually make things compared to those who pretty much only read about making things?

Enjoyed your post Megan, but then I always enjoy a mystery.

http://www.woodworkingwithajo.com

If you could obtain (that I fondly remember from my misspent youth) enough back issues, and read “What sort of man reads Playboy” I’m sure it would give you clues.

This dude was reading it:

http://www.toolsforworkingwood.com/store/blog/102/title/The%20Earliest%20Subscriber%20to%20an%20English%20Woodworking%20Magazine

So Dr. Fitzpatrick (to be), do you plan to stay with your burgeoning woodworking career once you achieve that lofty goal? Or, will you go off to the dusty halls of academia to examine the heavily constructed tables of the institutions libraries and classrooms? Certainly there must be more dissertations that can be prepared on the woodwork of academic institutions.

It might be worth looking at the subscribers to Thomas Chippendale’s Director and draw a corollary between who was receiving his serial as compared to Moxon’s. I’ll dig into my books on the subject and see if I can dig up a list of the original subscribers as well as supplemental subscribers. I think, in the end, both were probably more geared to the same audience than we might think today.

Well Someone’s writting a paper. What will your degree be in? (By dissertation I assume you’re going PhD.)

Megan

My current lint of thought points to Moxon having written Doctrine for purchase by the elite, such as the members of the Royal Society and by those with cash who might be having homes built for themselves. The scant records indicate that at times he complained that if not enough serial issues were to be sold, that he would cease printing, where-upon he urged his contacts, who by an large were the elite who bought his scientific machines and maps, to subscribe!

While the Guild structure was rapidly waning, Moxon, who came from a somewhat rebellious family, saw no problems with publishing a book about so-called trade secrets for use by the home owner.

This would make Doctrine more of an early “how-to” book rather than an apprentice guide.

At least that’s my current take on it. I’m yet delving into current literature to determine if anything new has turned up on Moxon and his contemporaries.