We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

I know there’s lots of Arts & Crafts fans out there reading Popular Woodworking Magazine and the “Editors’ Blog.” But did you know that makers from the period took their cues from much earlier periods?

Prior to William & Mary (1690ish to 1720 or so) most furniture was joined – meaning it was put together with mortise-and-tenon joints (the dovetail thing really became the predominant case joinery method in the W&M period). The other thing you’ll notice about a good bit of that furniture is it has a rather ecclesiastical appearance. Spend some time roaming through 17th-century churches and you’ll see what I mean.

The furniture was pretty straightforward – kind of squarish without a ton of realistic ornamentation. I’m not saying it’s dull or boring; in fact, it’s one of my favorite periods of furniture. What I find interesting is that you can see the base forms of future styles sitting there staring you in the face.

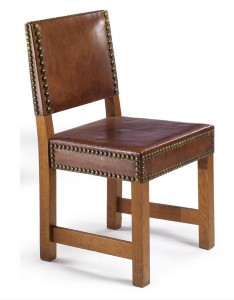

Something else I find interesting is that fans of Arts & Crafts furniture and decorative arts see the style as being something entirely new and unique. If you look at the first chair in this post, can you see how it relates to the Cromwellian chair? Granted there are a few decorative elements that differ, but the overall design is pretty similar, you’ll have to admit.

Keep the maker of the second chair away from the lathe and you’re looking at nearly the same piece just 250 years apart (give or take). I know, there are a few extra stretchers on the older chair but I want you to look at overall form, not the details. That concept is going to be important as you progress through this post.

Chairs, while fairly common, are not the only form of mission furniture that shares its roots with earlier pieces. When you look at chests you’ll see some base similarities as well. Take the two examples below, both are what today we would call blanket chests – the Stickley chest is a slightly stylized version of the Jacobean chest from Pennsylvania.

Both are joined chests (it’s a mortise-and-tenon thing, remember), which means they both have corner posts that form the foundation. The posts are joined by rails that capture flat panels. Sure the stiles that break the Stickley chest’s front into three separate panels have a bit of flair to them but they are basically the same. Remove some hardware from the Stickley chest and add a couple of drawers and we’re exactly where we were with the two chairs above.

If you really want to study historic furniture design, take a look at the precious metal smiths of the time and their work. They tended to be more on the cutting edge of design than the folks making furniture. This means you can see furniture forms in brass (and yes, I know brass is not a precious metal), silver and gold earlier than you can in tables, chairs or chests.

When I started looking for photos for this post I came across the Stickley wall plate below and instantly thought of alms dishes from the 16th and 17th centuries. Again, look not at the decorative details but the general form and you’ll see serious similarities.

I’m not criticizing either style of furniture here. In this, and all the “Design in Practice” posts I’ve done, I am trying to get you to look at things differently. Styles are related and there’s a progression. Things are recycled and repackaged constantly. If you look at each style as building upon the previous styles, you’ll learn to appreciate all of them to a greater degree.

The Arts & Crafts movement wasn’t just a rebellion against the mechanization of the Industrial Revolution driven Victorian designs – it was a harkening back to a simpler time when the forms played a greater role than the ornamentation. Even that movement itself was a repackaging of what happened as style transitioned from the Chippendale period into the Federal period. Fashion shifted from Rococo furniture with its lush, realistically carved vegetation to the simple, inlaid furniture of Hepplewhite. Everything old is new again.

For more 17th century inspired Arts and Crafts projects, check out Popular Woodworking’s Arts & Crafts Furniture.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

A problem with Arts and Crafts furniture is seeing it in isolation from the larger movement. It was really about creating an environment, a life style based on an overly romantic and certainly a unrealistic fantasy of life in a Medieval society (minus the plague). It was driven by utopian philosophy, all controlling architects, and sunshine socialists. I think the true spirit of the movement is more clearly expressed the amazing textiles, pottery and stained glass. As to furniture the term Arts and Crafts pitches a very large tent. It needs to be to cram Mackintosh, Stickley and the Greene brothers into the same style mold.

Rant over.

Thanks Don

Some of the difficulty in discussing comes from ignorance (Ever try getting an answer to what makes a particular furniture style?), some from terminology. In paragraph four you ask us to separate ‘design’ from ‘decorative elements’. it might be easier if you ask us to separate ‘structural design’ from ‘decorative elements’. Not that structural design is better defined, but it is clearer to me.

I’m hoping Chris’ upcoming book on furniture of necessity gives us a starting point for defining and discussing structural design.

There’s a lot of work/writing to be done here but it’s got to be done from a well-defined base to lead to discussion rather than argument.

So when can we expect to see chair projects from you in the magazine?