We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Unlike Wallington. I enjoy time spent at my craft – but turning is just part of my livelihood.

Trade dangers revealed in 17th-century journals.

I thought of Nehemiah Wallington (1598-1658) when I set up my lathe in my nearly finished workshop. A few times a year he pops up in my mind. He was a turner in Puritan-era London, and as unhappy a soul as you might meet.

I know of him through Paul S. Seaver’s book “Wallington’s World: A Puritan Artisan in Seventeenth-Century London” (Stanford UP). Wallington kept journals and notebooks, more than 2,600 pages of which survive, that are the material upon which Seaver wrote his book. While Wallington (and Seaver) concentrated on larger issues of the day – religion and politics among them – I scoured the book for references to Wallington’s trade.

Look Out!

’Ware falling chairs. A turned chair to the head would be painful.

Most of what we find in Seaver’s book mentioning the turner’s trade is about the workshop as a perilous place. Wallington recorded several brushes with near fatalities, and praised God after each close call.

One incident involved an apprentice, Theophilus Ward, who, while “showing chairs in the back room, dislodged a heavy one with his ‘bustling’ about, apparently one at the top of a stack, which crashed down into the shop through the doorway and demolished a powdering tub that Wallington was in the process of selling to another customer. ‘It was God’s great mercy that it hit none of us, for if it had, it would have maimed us, if not killed us.’”

Much of this quote is Seaver, not Wallington, so the chairs might not actually have been in a stack. Regardless, turned chairs of the period can be quite heavy, and I wouldn’t want one to fall on me – from a stack or not.

In another incident Wallington mentioned, “‘My sweet child Sarah was playing in the shop, and as I was shewing of bed staves’ to a customer, a huge ash log, propped against the wall, was dislodged and fell towards Sarah and ‘had I not by God’s providence caught hold of it – it would have knocked her down and killed her.’”

Furniture historians have often pondered what bed staves are, never having seen any surviving examples, but we all know what a “huge ash log” is, and that it would hurt if it fell on you.

One more. I include this so we don’t feel so alone in our haste making tool handles. “Nehemiah Wallington’s brother-in-law was chopping wood in the garret and the hatchet head had come off and fallen three stories down the stairwell to the shop, again missing everyone.” So tool handles shrunk back then, too; it’s not just a modern problem. Maybe they never did make them like they used to, after all.

Know Your Tools

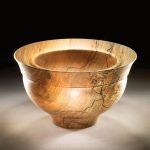

A hook. Here, I’m using one of the “dishturners’ tools,” specifically a hook, to hollow the inside of this bowl. The lathe’s power cord is wrapped around a mandrel fitted into the bowl.

My lathe is a simple machine, framed in oak and fastened with wooden wedges and iron nuts and bolts. I’ve had it since 1994 and am quite accustomed to its idiosyncratic traits. It’s a pole lathe, with one upright extended above the bed to form one “poppet” and the other moveable and secured with a wooden wedge. The workpiece is fastened between the centers of the lathe, which are mounted in these poppets.

In 1643, Thomas Baynley died en route to New England. His goods were inventoried in Boston, and among his tools were “one skrew & a pin to turne.”

This refers to the points of a pole lathe, as described by Joseph Moxon some years later in his book “Mechanick Exercises.” A treadle or great wheel lathe needs a drive center at one end to transfer the action to the workpiece.

Baynley also had “two gouges & two hooke tooles” and “3 turning chesils.”

More typically, period inventories are less specific, like the “dishturners tooles” owned by John Frizby of New Haven in 1694.

I mostly use my lathe for joined furniture parts: legs (or “stiles”) of joined stools and chairs, applied turnings for casework and other small bits. I do make turned chairs on it, but not enough to be efficient at it. The same holds true for woodenware.

Applied work. Not all turnings stay in the round. Here’s a pair of split turnings glued and nailed to a joined chest.

For me, the most compelling quote in Seaver’s book is in Wallington’s own words: “At night after examination how I have spent the day, after a chapter read I went to prayer with my family; then I went into my shop to my employment more out of conscience to God’s commands than of any love I had unto it.”

This quote leaves me thinking two things. One is that it figures that the only period artisan who wrote anything I have ever seen about his trade is a poor, unhappy craftsman with no real interest in his work. The second is how lucky I am today to be able to spend my time making things in wood with simple tools, and both provide for my family and enjoy it at the same time.

This article originally appeared in the __ issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.