We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Jim Moon produced a faithful replica of this iconic cabinet, with a decorative touch or two of his own.

In the world of historic furniture-making, Jim Moon casts a long shadow. He is not only a highly respected furniture maker but also has the remarkable output of someone who works hard and fast.

His entree into serious woodworking was as a medical student (he’s now a surgeon) four decades ago, when he wanted to give a tall-case clock as a gift. But, he recalls, “there weren’t many good antiques in South Dakota, and certainly none I could afford, so if I wanted one, I had to make it myself.”

He befriended a cabinetmaker who sold him the walnut to make his clock and mentored him in making it. Eventually, Moon bought most of that cabinetmaker’s machinery and embarked on a lifetime of woodworking with an output that can justly be described as nonpareil and prodigious. The Moon home is a gallery of his exquisite work, and he jokes that he might need to start rotating the pieces between the living spaces and the attic if he makes any more.

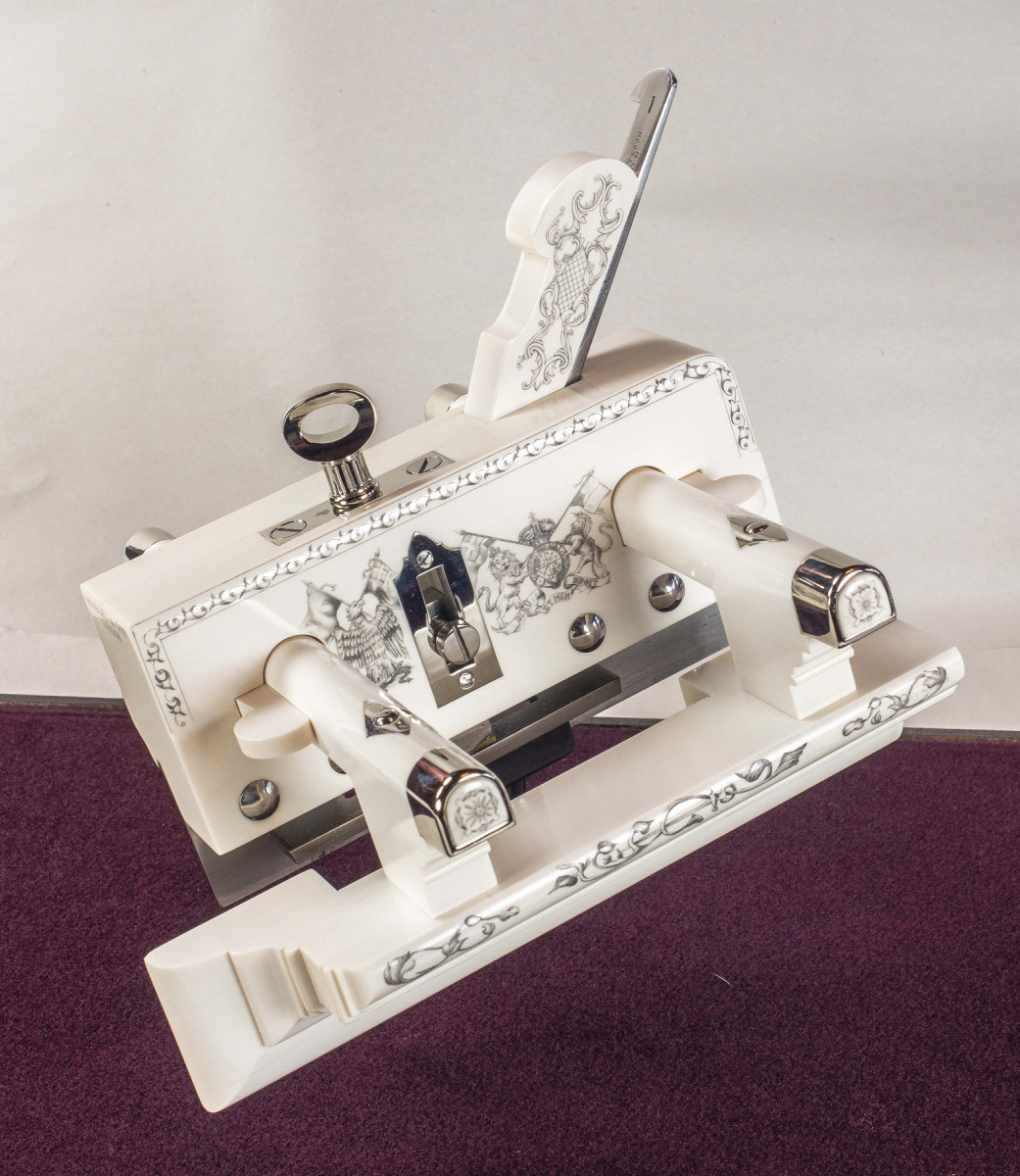

Plow plane. Lessons learned in restoring and making plow planes served Jim Moon well when reproducing the Studley tool cabinet and its contents. This ultra-showy model involved exceedingly intricate work in exotic materials.

As Jim’s craft gravitated toward handwork alongside his machine work, he caught the incurable affliction of collecting (mostly vintage) hand tools. His passion for plow planes resulted in acquiring, restoring and eventually making hundreds of them.

Those projects integrated high-precision hand and machine work in exotic materials, and I can attest that gawking at his guest room/plane exhibit hall is a marvelous and humbling experience.

This foundation made him unusually well-prepared to replicate Henry O. Studley’s iconic tool cabinet – but with just a 1988 poster of the 19th-century piano maker’s cabinet as his guide, he didn’t think he possessed enough detailed information to undertake the project. So the idea sat simmering on his back burner for decades, unstirred until the summer of 2015.

Enter the Author

Chippendale. This “bucket list” highboy was, Jim said, his greatest woodworking challenge – until he met Studley.

Like almost everyone else in the woodworking universe, my introduction to the remarkable Henry O. Studley was through a single tantalizing image of his tool cabinet on the back cover of Fine Woodworking in 1988 (coincidentally the only issue of that publication to ever include one of my articles). I bought the poster. Years of looking at the gently fading poster hanging in my shop only whetted my interest; eventually I spent more than 30 days with the cabinet during the five years I was researching it for “Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Workbench of Henry O. Studley” (Lost Art Press, 2015).

At a 2015 presentation to the Society of American Period Furniture Makers (SAPFM), I recounted the tale of creating that book, and of the Studley Collection exhibit in Amana, Iowa, that spring, which allowed visitors to come within inches of the iconic artifacts. One attendee took the collective interest to a whole new level.

Jim and I chatted at that SAPFM event, mostly about the amazing “bucket list carved Philadelphia highboy” he’d built in the preceding few months – but as a result of my presentation the seed for a new project had been planted.

He left the conference with a copy of the book and a new focus for his remarkable energy and ability – to replicate Studley’s incomparable tool cabinet and the previously unknown (to him) workbench. Jim’s wife, Mary, chuckled that after that conference, she “could see the wheels turning in his head all the way home.”

Once word of his new project started leaking out among our woodworking community, the typical response was, “Jim Moon? Studley? Of course!”

The Tools

User-modified. Just like Studley’s originals, this set of bench chisels has owner-made rosewood handles and ferrules.

Jim is a tool guy. Not only does he use them skillfully, but he has amassed a broad and excellent collection of historic tools, and he has fashioned some of the most remarkable tools, mostly planes, that I have ever encountered. It is clear that he was perfectly suited to channeling Studley in creating and modifying tools.

Even before getting back home Jim began to devour my written information and Narayan Nayar’s sumptuous images in the book. Then he got down to the serious business of making a version of the tool cabinet to hold his own collection that, much to his delight, included many of the same tools as Studley’s. One of his hurdles was simply trying to remember where such-and-such an old tool was in his boxes of treasures obtained during tool-meet tailgating expeditions.

Using the tool inventory in “Virtuoso,” Jim pursued the missing ones through the Mid-West Tool Collector’s Association, online auctions and forums, and tool mongers including Patrick Leach and Martin Donnelly. And like Studley, Jim made or modified tools to fill out the roster when necessary.

His toolmaking ability was integral to the project, because some of the tools are so peculiar that we don’t even know their function, much less their availability in the market, and some are so rare and collectible that making replicas was the most sensible route. Jim fabricated those from scratch out of raw metal stock, turning them on his precision machinists’ lathe or machining them on his compact vertical boring mill. He also in some cases modified contemporary tools, including a set of rosewood-inlaid machinist’s squares.

Like Studley, Jim has a thing for Brazilian rosewood, and has collected bits and pieces of the rare exotic lumber for decades. Thanks to this passion he was able to make replica hammer handles and turn a graduated set of chisel handles just as Studley did more than a century ago.

The Cabinet

A shop divided. Jim has a well-outfitted machinists’ set-up for toolmaking opposite the woodworking side of the shop.

Using the dimensions and images provided in the book, Jim dove in using wood from his impressive stash, which includes some premium vintage mahogany. “I guess he hasn’t taken you upstairs to the lumber yard, huh?” said Mary during my visit.

Jim led the way upstairs to the attic above the large shop and garage, where several hundred square feet of floor space is filled with stacks and stacks of cured lumber awaiting the eventual trip down through the hatch to the shop – everything from flitch-cut pear trunks salvaged from local arborists (stock Jim calls his “curb lumber”) to select pieces of hardwoods, softwoods, and exotics acquired over decades.

Jim led the way upstairs to the attic above the large shop and garage, where several hundred square feet of floor space is filled with stacks and stacks of cured lumber awaiting the eventual trip down through the hatch to the shop – everything from flitch-cut pear trunks salvaged from local arborists (stock Jim calls his “curb lumber”) to select pieces of hardwoods, softwoods, and exotics acquired over decades.

As for making the mahogany case for the tool cabinet, “that was just a weekend project,” Jim says. “There’s no rocket science here. Just plain old stock prep and joinery.”

The details took much longer. Cutting, shaping and assembling the many subordinate units took many weeks of painstakingly tedious and delicate work.

Unladen. Here’s Jim’s completed tool cabinet, sans tools. Note the many niches and fittings, as well as the hinges, behind which are one or more layers of neatly fitted tool storage.

With the complete tool inventory and images in hand, Jim laid out each of Studley’s storage sections on a flat board to establish the precise location and orientation of each tool. For some of the proportions and divisions he wrestled with calculations and spacing for the niches and saddles before smacking his forehead with the realization that most of the images of the tool compositions contained machinist’s scales. All he had to do was transfer the space in question to the scale in the frame, and voilá – the problem solved itself.

With that information he fabricated all the dividers, moving frames, restraining fittings (the latter mostly in solid ebony) and imparted the remarkable detailing via ebony turnings, fittings and bandings inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory elements. The craftsmanship is outstanding in every respect, and includes a few additional decorative touches from Jim, including insetting pearl buttons into the face of each drawer pull.

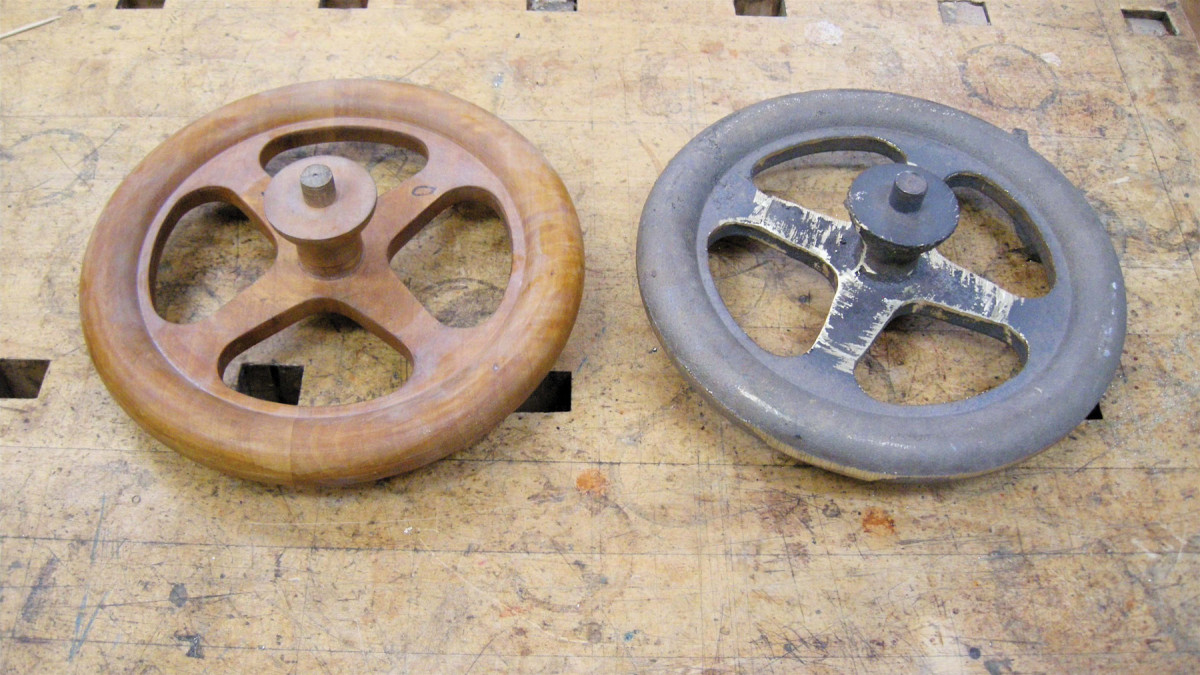

From wood to iron. Jim made wooden patterns for the vise jaws and handwheels (shown here are the handwheels), then had the parts cast in iron and nickel plated before mounting them on his reproduction bench.

Jim says these add fun to the process, because he finds making exact, undeviating copies pretty boring. Like all creative people he revels in imparting little bits of his own vision into the details. Along that line, the contents of a few of the drawers reflect his own tool choices rather than Studley’s – an entirely sensible approach.

Drawers. The many drawers in the cabinet are built with the same painstaking care and skill as everything else.

For the interior spacings he was especially challenged by the minuscule tolerances of the layered three-dimensional arrangements – the parts that move all have to clear their surroundings and the tools have to avoid interfering with others, layer upon layer. Systematically, and with vigorous ongoing and sometimes pungent verbal commentary, he says, he worked his way through every instance of the pieces not fitting and moving perfectly until he resolved the problem.

Jim’s most frustrating moments revolved around the closing of the two cabinet sections themselves; he could get the “doors” to about 1⁄8” apart, then they would close no farther. With flashlight and magnifiers he tracked down the offending components and rectified the problem, moving some fittings slightly, notching some mouldings here, shaving a slight bevel there, until they fit together perfectly.

Jim is convinced through his faithful mimicry of Studley that the master encountered the same issues 125 years ago. We agreed that if he did not, it’s probably proof that Studley was an alien or time traveler from a technologically superior world.

The Workbench & Vises

Personal tools. While some of the drawers are fitted and filled a la Studley, like this arrangement of spoon bits and specialized brace bits, others contain some of Jim’s favorite personal tools.

Studley’s workbench base is lost in the mists of history, probably sold as a dressing table at an estate auction, but the original top is a resilient survivor now residing on a splendid base built by the collection’s owner (who wishes to remain anonymous). As a workbench junkie myself (I have a possibly excessive nine benches currently in my studio, with at least five more in various stages of construction), I found Studley’s bench and vises to be every bit as enticing as the tool cabinet, and built a replica of the top for the exhibit (and later installed it in my shop). So I was delighted to learn that Jim was fabricating a complete bench to reflect the one in the collection.

Following the specs of the original top, Jim made his the same dimensions with the identical structure: two white oak laminae for the core with mildly figured mahogany faces trimmed with ebony edges. For the base, he followed the example of the owner of Studley’s benchtop in fabricating a kneehole cabinet with mahogany as the primary wood, but deviated from the earlier version by using pear as a secondary stock.

Following the specs of the original top, Jim made his the same dimensions with the identical structure: two white oak laminae for the core with mildly figured mahogany faces trimmed with ebony edges. For the base, he followed the example of the owner of Studley’s benchtop in fabricating a kneehole cabinet with mahogany as the primary wood, but deviated from the earlier version by using pear as a secondary stock.

He also fabricated wood patterns for the wheels and jaws, then had them cast by a foundry before filing and polishing, and had them nickel plated.

Decorative Details

Details.

Other details replicated include mother-of-pearl and ebony inlay and toggles that hold various tools in place.

The Masonic crest on Studley’s cabinet proclaimed his membership in the organization, and provided a logical location for dividers.

Epilogue

Lift here. Here, Jim shows some of the many moving parts of his tool cabinet, which now hangs in his study (an elegant room lined with paneling he made out of wormy chestnut salvaged from a local demolition project).

Jim didn’t keep track of the hours he spent on the cabinet, noting only that it commenced in mid-June and was completed by the end of the year. By massaging the rough estimates he gave of available shop time between office and surgery hours, combined with two days each weekend, my rough guess is that it took 600 to 800 hours for the project as a whole, workbench included.

Perhaps no woodworking story of mine has a better ending than this one. I first visited Jim when he was nearing completion of this project, to scrutinize the tool cabinet as he was building the workbench. I contacted the owner of the Studley collection to suggest that Jim would love to make a visit to see the original work in person. The invitation was proffered and accepted.

It was a craft-life highlight for Jim – he was impressed as only those who have seen the workmanship of Studley in person can be (if you were in Iowa, you know this feeling).

Fast forward to a weekend French parquetry class Jim took with me at my shop, The Barn on White Run. With little fanfare, he pulled from his car a velvet bag with the insignia of a fine whisky embroidered on it – but the real surprise was inside. The beech-infilled brass mallet is my favorite tool in the Studley set, and it was his pleasure, he said, to make a replica for me. I was speechless with appreciation, and it now sits in a place of honor in our home.

Jim’s chest now hangs over his replica workbench in his elegant paneled study.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.