We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

My life changed under the guidance of a master chairmaker.

This article originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Popular Woodworking

Have you ever walked into a brand new place and instantly felt completely at home? That’s the way I felt the first time I entered Greg Pennington’s Windsor chair school just outside Nashville. The building was timber framed by hand out of solid oak Greg milled with his Wood-Mizer. Against one wall is his iconic floor-to-ceiling tool chest. In the center of the room is a Harmon coal stove, and surrounding all three sides of the building are windows, providing perfect raking light during daylight hours, and inviting the world outside into the cozy paradise within at night. Shave horses of all shapes and sizes litter the room, as do several Roubo-style workbenches, and the whole wall behind the fireplace is covered with dozens of antique drawknives, antique axes and saws.

1. Splitting and riving green stock is typically the first step in making a Windsor chair. This process also helps you learn about how wood works.

As if the classroom itself weren’t inviting enough, Greg’s mother also provides a home-cooked meal for lunches throughout the class. There’s always hot coffee in the back, and, if you ever run out of wood, you can mosey on back to the slab storage barn, stacked floor to ceiling with all manner of cherry, walnut, oak and maple. Greg’s school is what I’d wager most woodworkers would imagine heaven to be like.

It was there, more than a little burned out on woodworking after five years trying to “make it” as a furniture maker, that my excitement and passion for working with wood was reignited.

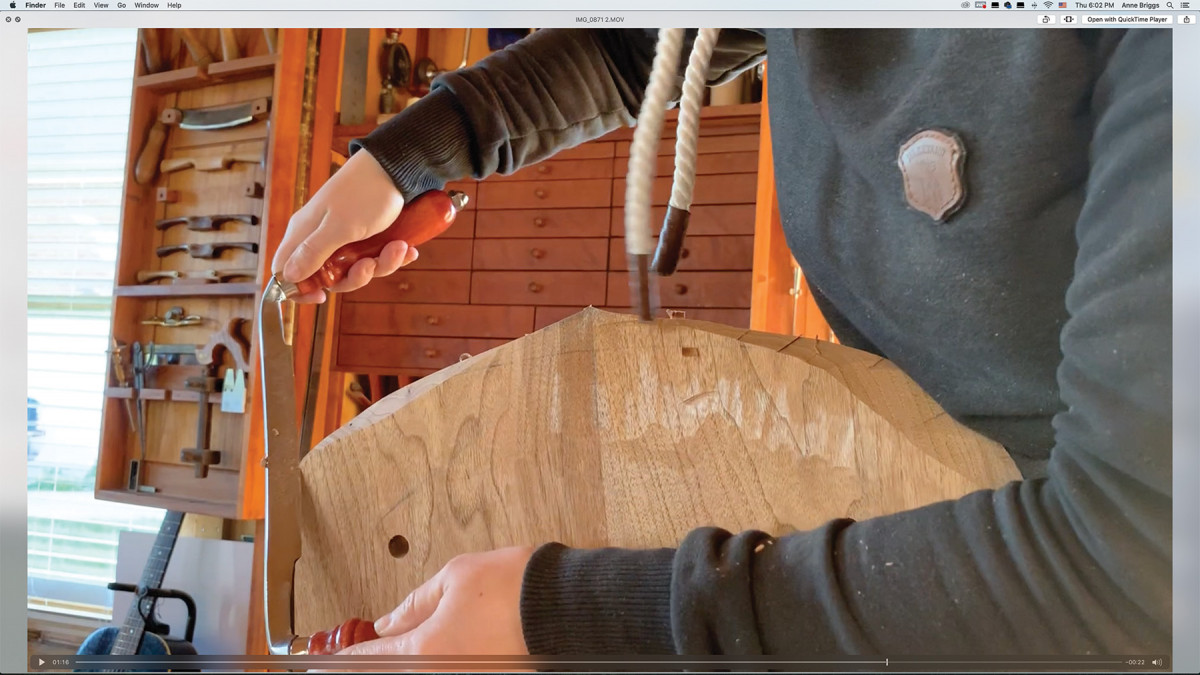

2. Shaping a crest rail on the shave horse. Most chair parts are roughed out here.

Chairmaking is very different than other forms of furniture making. Chairmaking requires its own unique tool and skillset. It is extremely physical, and, while the mind can wander during certain aspects of the build (hello, spindle making), it also requires an intense focus and problem-solving skills. There’s more than a little figuring required, but Greg makes the daunting process of finding an entire chair from within a small section of tree stump shockingly approachable.

Building chairs opened up a new, very physical, very engaging side of woodworking I hadn’t before experienced. I loved using a wedge and sledge to split the tree. Not only did it make me feel strong, it also helped me to understand better how wood works and how to get the most strength possible out of a single piece of wood.

Design

3. Rough parts after a few hours on the shave horse. It’s good practice to make a few extra spindles, stretchers and legs.

Though I was at Greg’s for a rocking-chair class, I decided to make a second chair in the evenings, entirely out of seasoned wood—both because of time constraints and because I just wanted to see how it would work.

4. Windsor chairs have lots of turnings, so you learn to be efficient.

Living in Seattle, I don’t have a lot of access to nice straight-grained green wood. Green wood works easier and turns faster, but air-dried wood, especially when selected and sawn in such a way that the grain runs along the entire piece, will retain just as much strength as riven wood and will take on a nicer finish right off the tool.

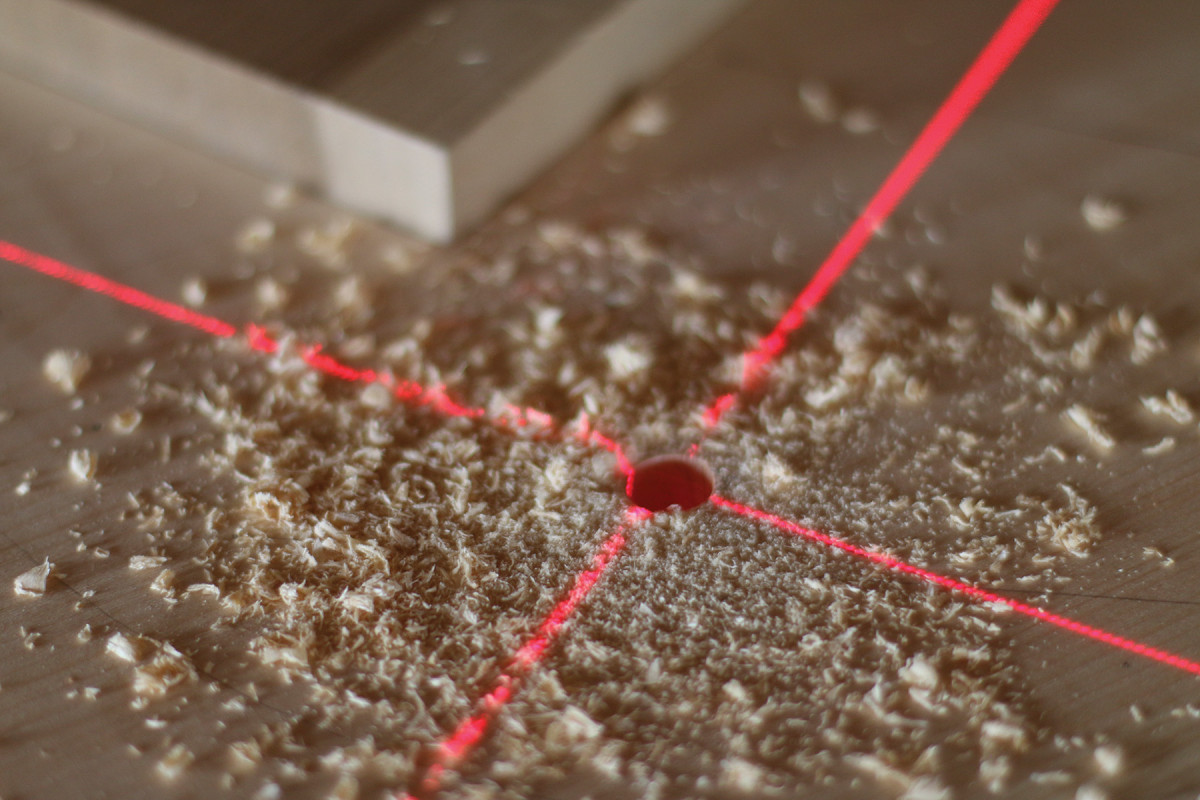

5-6. Drilling angled mortises is one of the trickier parts of building a chair.

I patterned this chair off of a Glen Rundell design I’d spotted in Greg’s shop. I was drawn to the pommelled seat, curved back and simple design. I wondered what the chair would look like with some of Greg’s double-bobbin legs.

First, you drill a hole, then you use a tapered reamer to give it a shape that’ll securely mate with a leg.

I only had three evenings in which to get the chair parts together, so time was of the essence, and the most important thing was getting the curved seat back roughed out, steamed, bent and set on a form to dry as long as possible.

Curved Back

7. Scooping out a seat is physical work, but sharp tools and working with the grain make things easier.

I chose a nice, straight-grained piece from the center of an air-dried walnut slab for the crest rail. I roughed it out on the bandsaw, then brought it down to near-finished shape using a Caleb James Monstershave (also known as an extra large spokeshave). Since the walnut was dry, it needed to be steamed for about 50 minutes to ensure full penetration. Greg and I teamed up to clamp both sides simultaneously to a laminated melamine form using squeeze clamps. Thankfully, the wood bent without a hitch, and we put it next to the wood stove for a couple days to aid in a quicker drying process.

Windsor Chair Cut List

No. Item Dimensions (inches)

t w l

1 Seat 2 x 20 x 20

4 Legs* 1/2 x 1/2 x 18

3 Stretchers* 3/4 x 3/4 x 16

4 Back spindles 3/4 x 3/4 x 24

No. Item Dimensions (inches)

t w l

2 Back arms/sides* 2 x 2 x 24

1 Back rail 5/8 x 3 x 20

These are rough, pre-shaping dimensions.

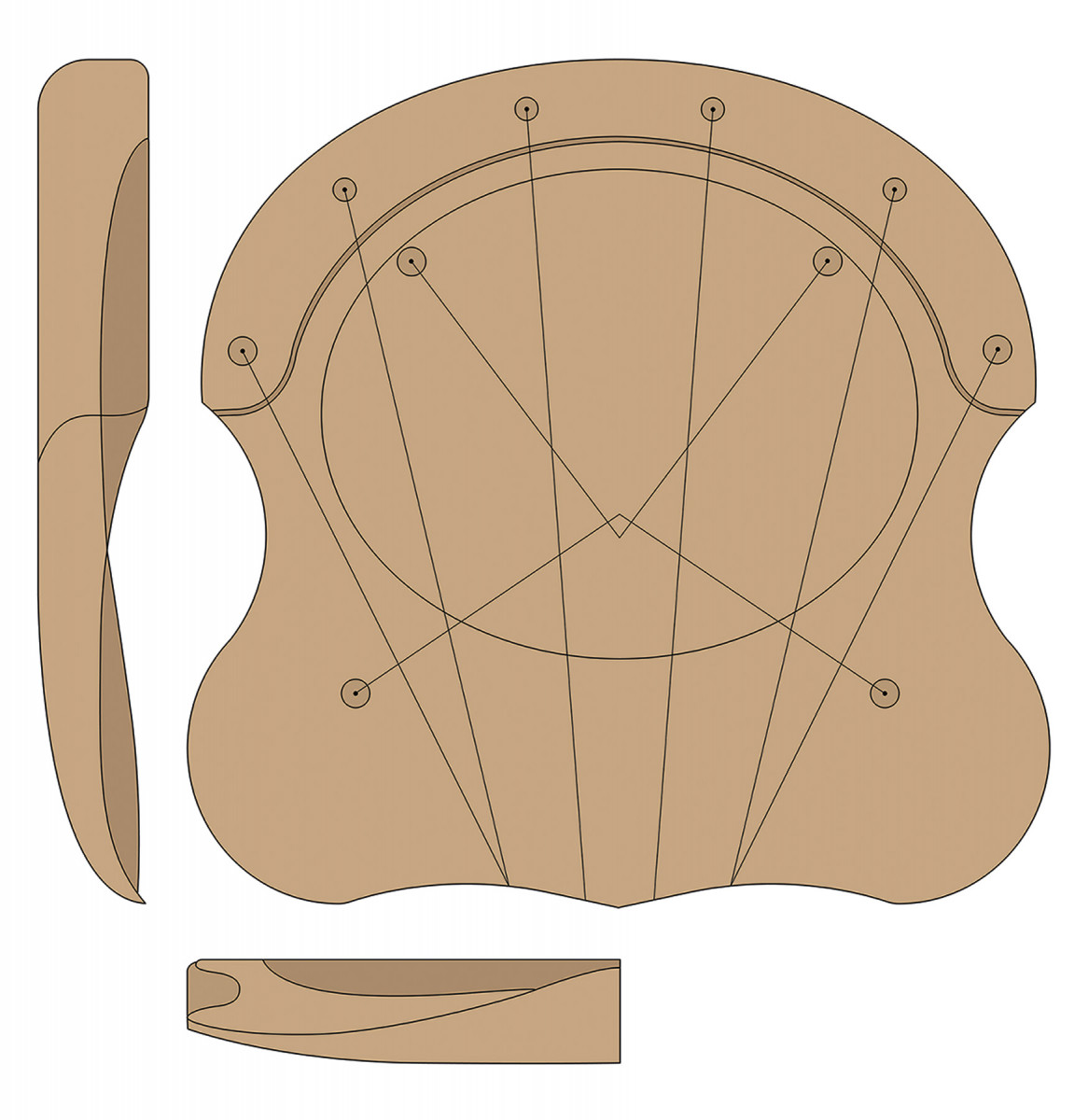

Back View

Side View

Front View

Seat

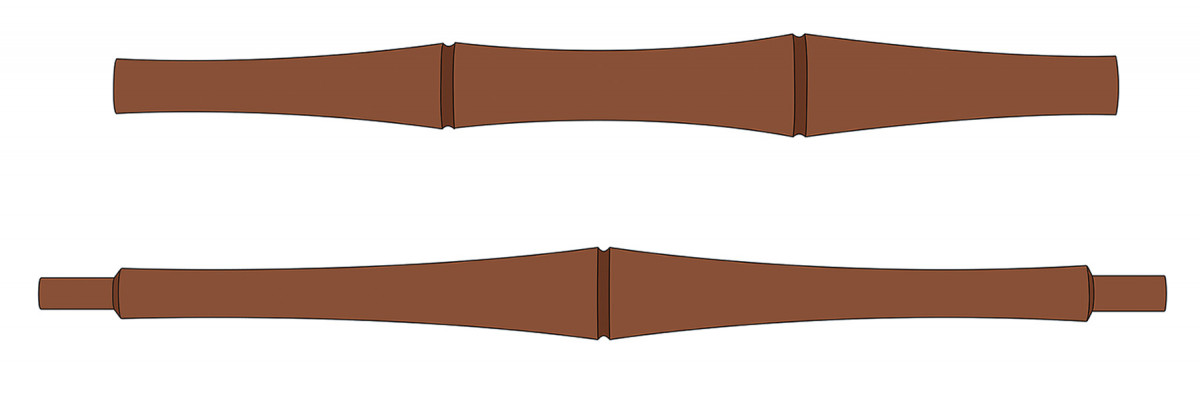

Leg (top) & Stretchers (bottom)

Back Rail

Turning the Legs

8. I carved the decorative gullet around the edge of this seat with a small V-shaped gouge.

With the back on the form, it was off to the lathe to turn the legs. Greg teaches us to use only five tools at the lathe: a roughing gouge, a Galbert Caliper, a parting tool, a story stick, and for the last step—the groove detail on the bobbins—a nice sharp skew. By the fourth leg, I had my bobbin leg turning down to 6 minutes and 40 seconds—but I think I’m a few hundred legs away from beating Greg’s sub-two-minute time or perfection level.

9. Here I’m using a gouge and mallet to trim the wedged legs.

The key to turning quickly is training your “eyechrometer” (a favorite Greg-ism) and getting really brave with your rough passes. It’s helpful to make all the matched parts in batches, because all the nuances and wasted movements become more obvious the more times each task is repeated. It took me a while, and a few botched legs, to get the hang of using the parting tool for that V-groove detail on the bobbins. (The key is light cuts and an extremely confident grip on the tool.)

10. Scooping a seat by hand is vigorous work. Do what it takes to get in the right position.

With four legs and three stretchers done, it was time to work on the seat. Greg had a gorgeous two-piece butternut seat blank ready to carve.

The Seat

11. Refining the roughed-out seat is done with a travisher.

I patterned the seat as closely as I could to Glenn’s, aiming to achieve that same pommelled look. Because I didn’t have a paper pattern to use, a lot of the seat design had to be done by eye. The thing is, though, a lot of chairmaking can be done by eye. Greg has a phrase he uses quite a lot in his classes: That’s chairmaker perfect. It’s a freeing thing, to throw some of the machinist-precise measurements and extremely complex compound angles out the window and just eyeball it.

12. I used ash wedges (sized to fit the top of the tapered mortises) to secure the legs.

The next step was to drill and ream the seat. Greg figured out a way to make this impossible step just a little more possible, and a whole lot more exciting and photographable (yes, that’s a word) by introducing lasers into the process (see “Shedding Light on Compound Angles” in Popular Woodworking #232).

13-14. With the seat roughed out, a drawknife is used to refine and lighten the seat, both top and bottom.

After the seat was drilled, I laid out and carved in the gullet, drilled the low points of the seat to act as a stop point for the rough carving process and got to work roughing out the seat with a nice sharp scorp. Having your work secured well at an accessible height and paying close attention to grain direction at this step is paramount. Once the seat is carved to depth, it’s time to take it to the bandsaw to cut down to the final shape. It’s important to wait until the seat is mostly carved for this step, because removing the front square bits of the seat blank will give you less area to clamp for the carving portion.

With the rough stock removal done, it’s time to move to the travisher. Claire Minihan and Alan Williams make excellent tools for seat refinement. Caleb James, HNT Gordon, and Dave’s Shaves make excellent round bottomed spokeshaves that help to further refine the seat and get into tricky spots.

With the rough stock removal done, it’s time to move to the travisher. Claire Minihan and Alan Williams make excellent tools for seat refinement. Caleb James, HNT Gordon, and Dave’s Shaves make excellent round bottomed spokeshaves that help to further refine the seat and get into tricky spots.

A drawknife removes the bulk of the waste from the bottom of the seat and the sides. With all the tricky grain changes, sometimes a sharp-curved scraper is the only way to tame the wild spots.

About Greg Pennington

In his past life, Greg was a diesel mechanic. He earned his stripes as a chairmaker studying with Curtis Buchannan and teaching alongside Peter Galbert. To this day, he processes and turns a lot of the chair components for Curtis’s classes. To that end, Greg’s gotten his production turning game down pat, turning a chair leg at an average rate of one minute forty seconds. After a week in his shop and a lot of patient instruction, I was able to turn a leg in six minutes forty seconds, but I’m not sure I have the tenacity required to turn enough legs to shave five full minutes off my time and simultaneously add any level of Greg’s perfectionism into my own turnings.

Perhaps it’s his drastic career change, or the fact that humans truly come alive doing what they are “supposed” to be doing, but Greg has a down-to-earth manner about him that makes him a truly gifted teacher. He has an uncanny ability to read people and customize each explanation to cater to the knowledge and experience base of every student with whom he’s interacting.

Legs and Stretchers

15. The legs for a Windsor chair are glued and wedged in place from the top.

After the seat is finished, it’s time to test fit the legs and drill out the mortises for the stretchers. It’s important at this step to make sure to align your legs the right way with the seat to accommodate wood movement so the seasonal expansion and contraction of your legs doesn’t split your chair seat. The proper way is for the long grain of the legs to be oriented perpendicular to the long grain of the seat, with the wedges parallel with the front line of the seat.

Greg uses rubber bands around the chair legs to act as perfect sight lines for the drill when drilling for the stretchers. A piece of blue tape on the drill bit indicates the final depth of the hole and prevents accidentally drilling through the entire piece. The V-grooves in the double-bobbin style legs make this step a breeze, because they give the tip of the drill bit a landing point.

Using two barbeque skewers held parallel to one another, it’s easy to ascertain the final length of the stretchers, which were purposefully left long. Those barbeque skewers will come in handy again when determining the final length of the back spindles later on. I cut the stretchers to final length, then glued the two side stretchers to the left and right legs using warm hide glue. The back stretcher will go in simultaneous to the seat/leg glue-up.

16. The spindles for the back are just glued in place, but the arms are glued and wedged from the bottom.

At this point, I knew exactly what the final orientation of the left and right legs in relation to the seat would be, so I marked perpendicular wedge lines and cut them down the length of the mortise with a handsaw. Because I was using ash as a contrasting wood for this chair, I made up some ash wedges and fit them using a small block plane.

Then comes the stressful part: gluing up the seat, legs and stretchers. Remembering all the proper orientations, a second set of hands is helpful for this step, especially when glueing the back stretcher and set in simultaneously. A band clamp can help in a pinch. Glue only one side of the wedges so the tenon can move seasonally and not pop the glue joint. Use a metal hammer to drive in the wedges and listen for the sound change when the wedge is fully seated. Then breathe a big sigh of relief; the hardest part is over.

Back and Spindles

17. Putting all the pieces together. It’s surprising how quickly a pile of pieces turns into a chair.

I turned two arms on the lathe and carved the ornamental flats in both arms using a drawknife. Then, I selected a straight-grained ash board and cut spindle material out with the bandsaw. I rough turned them, then refined the shape using a spokeshave. When sizing spindles, the Hamilton Spindle Gauge comes in extremely handy, taking all the guesswork out of the sizing process.

I waited until the last possible second, then removed the curved back from the form by the wood stove, hoping it had had time to dry enough to retain its shape. I finished shaping it and used it to lay out the mortises in the arms. I drilled out the majority of the waste, then chopped it square with a sharp chisel.

Once my mortises were square, I did the final refinement and fitting of the chair back into the arms, did all the final shaping, and drilled offset holes in the arms and back to create a drawbored joint that would pull my chair-back tenons in tight and hold them there for a century or two to come. I made ash drawbore pins, once again as a contrasting detail using a dowel plate. I then set them aside and laid out the spindle placement on the seat and chair back using a set of dividers, my eyechrometer, and a series of visual trials.

I dry fit the arms and curved back, set them in the chair, and used a spindle balanced on the chair back as a sight-line to drill the spindle holes into the seat. I used my eyechrometer to guesstimate the angle to drill the spindle holes into the curved seat back. I used the skewer stick trick to determine the final length of the spindles, cut them to the proper length, did the final sizing and shaping, then said a little prayer and heated up the glue pot once more.

Finishing Touches

18. One of my fully assembled Windsor chairs. The continuous arm is mortised and pinned in place, ready for final tweaks before finishing.

The back spindles are just glued into place, but the arms are wedged from the seat bottom. Thankfully, it all went together without a hitch.

Then came time to level the legs. This chair wants to recline ever so slightly back. That meant cutting the legs in the back down by about an inch and leveling the front legs. This process is done by using wedges to make the chair sit level, then using a scrap piece of wood as a scribing gauge of sorts to leave a “level” mark around each of the four legs. That extra material can be hand sawn off, planed down, or, Gary Rogowski has a handy trick of cutting them level using the table saw.

I did some final seat refinement and sanding, and prepped for finish. I really wanted to let the wood of this chair speak for itself, and Greg recommended an equal three-part blend of mineral spirits, spar varnish, and boiled linseed oil.

Making a chair is, I think for most woodworkers, a major benchmark for progression in their craft, and something I think every woodworker should try—at least once. Understanding the whys and hows of chairmaking will change a “square minded” furniture maker’s craft. From considerations of wood movement to deriving the most possible grain strength out of a piece of wood, designs could become more functional, more graceful, lighter, more elegant, longer-lasting.

Taking a chairmaking class takes an impossibly daunting task and makes it approachable. Spending a week in a quiet chairmaker’s shop with a group of makers is so life-giving. Even though chairmaking is very physical work, I find these classes to be incredibly restful. There’s time to sit and think, to process. In the company of other like-minded individuals, working toward a similar goal, passions are reignited, new inspirations found and new friendships forged. If you have the chance to take a chairmaking class, I can’t recommend it highly enough. If you have a chance to take a class from Greg, let me know—I’ll probably hop on a plane and join you!

Anne Briggs is a woodworker, maker and organic farmer. You can learn more about her work at anneofalltrades.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.