We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Werner Duerr continually drove one concept into our heads: “Do everything by machine until you come to a point where the only way to do it better is by hand.” Ever concerned with our productivity, the cabinetmaking and carpentry vocational teacher tried his best to instill in his students a sense of urgency in the work.

Werner Duerr continually drove one concept into our heads: “Do everything by machine until you come to a point where the only way to do it better is by hand.” Ever concerned with our productivity, the cabinetmaking and carpentry vocational teacher tried his best to instill in his students a sense of urgency in the work.

I’ve tried to keep true to that philosophy throughout my career, using the most efficient method I know to do any task. I cut my dovetails by hand but have no problem using a hollow-chisel mortiser and a table saw to make a mortise-and-tenon joint. To me, the concepts are clear: A dovetail is a joint that is often visible and represents the “craft” of the worker; a mortise-and-tenon joint is seldom seen and represents the “structure” of the piece being made. While not a literal translation of Werner’s mantra, it makes sense to me in relation to how I work. The idea is use the best tool for the job – regardless of whether that tool is muscle or electron powered. How you define “best tool for the job” is subjective based on intent, philosophy and deadline.

This concept holds true not only for joinery but for surface prep as well. For instance, I scrub plane or scrape, all my secondary and interior surfaces when building case pieces (most other pieces as well). My intent is to simulate the surfaces left by the original makers of the pieces I’m copying (or adapting). I know lots of woodworkers who figure if the surface isn’t going to be seen that it makes no difference if you do anything to that surface or not. I’ve seen everything from straight out of the planer to sanded perfectly smooth to still having circular saw marks from the sawmill (I’ve even seen pit saw marks on the interiors of some period pieces).

This concept holds true not only for joinery but for surface prep as well. For instance, I scrub plane or scrape, all my secondary and interior surfaces when building case pieces (most other pieces as well). My intent is to simulate the surfaces left by the original makers of the pieces I’m copying (or adapting). I know lots of woodworkers who figure if the surface isn’t going to be seen that it makes no difference if you do anything to that surface or not. I’ve seen everything from straight out of the planer to sanded perfectly smooth to still having circular saw marks from the sawmill (I’ve even seen pit saw marks on the interiors of some period pieces).

The same holds true for exterior surfaces. I tend to scrape or plane my exterior surfaces then I sand. I know there will be those out there who stand aghast at the thought of sanding a scraped or planed surface – but it’s my piece and my method; you are free to choose your own. I sand to get consistency in my surfaces so when I finish the piece I don’t end up with a variety of colors and textures.

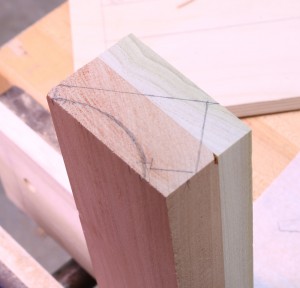

I was recently working on some cove moulding and heard Werner’s voice ringing in my ears from the outset. While drawing out the profile, I began thinking of how to make the moulding efficiently. Although I have No. 18 hollows and rounds, the profile is larger still. That doesn’t mean I couldn’t use a handplane to make the moulding; it means it may not be the most efficient way. Looking through the shop’s collection of router bits failed to produce the appropriate radius either. The table saw was looking like the most likely candidate for making this profile.

I was recently working on some cove moulding and heard Werner’s voice ringing in my ears from the outset. While drawing out the profile, I began thinking of how to make the moulding efficiently. Although I have No. 18 hollows and rounds, the profile is larger still. That doesn’t mean I couldn’t use a handplane to make the moulding; it means it may not be the most efficient way. Looking through the shop’s collection of router bits failed to produce the appropriate radius either. The table saw was looking like the most likely candidate for making this profile.

Typically after running a cove on the table saw, I would use a gooseneck scraper and a random-orbit sander (I’m sure I’ll demonstrate this at some point but keep reading…) in combination to prep the surface. This moulding, however, was an in-between size that just made things difficult.

Typically after running a cove on the table saw, I would use a gooseneck scraper and a random-orbit sander (I’m sure I’ll demonstrate this at some point but keep reading…) in combination to prep the surface. This moulding, however, was an in-between size that just made things difficult.

Although making the moulding entirely with a No. 18 round wasn’t necessarily the most efficient use of my time, using it to clean up the saw marks left behind by the table saw might be. I locked the moulding onto the bench between the tail vise and a dog, set the plane to take a fine shaving and off I went. In less than 15 minutes I had four sticks of cove moulding, each 8′ long, with machine marks removed and completely sanded prior to installation.

I’m sure, when he reads this, Werner will be proud.

To learn more about how to make a cove moulding on the table saw, try this digital download from Glen Huey.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Chuck, there must be one other factor thrown into the mix…tool availability. In my shop I use a mix of hand and power tools, mostly hand for various reasons. The biggest reason I use hand planes to square up stock is that I don’t have room in my shop for a good quality jointer. But, once one face is flat and one edge square to it, it’s off to the thickness planer and table saw to finish the job.

So because I’m a hand tool zealot does this mean I can tell Heather that Chuck thinks I’m romantic?

Speed and efficiency often meant the difference between having a job and being unemployed, not just in a cabinet shop, but just in just about any trade. That is as true today as it was in the 18th century. So if “they” had a table saw would they have used it? Yeah, because if the shop master purchased a table saw and brought it into a shop he would have expected and demanded his employees to learn how to use it, or they could go find a shop that didn’t use one and keep their ideals and tradition intact.

+1 on Mr. Duerr. I’m always amazed that people will spend half a day making a single-use, single-purpose jig or fixture to do a machine job that would take 10 minutes by hand tools.