Surprising Similarities

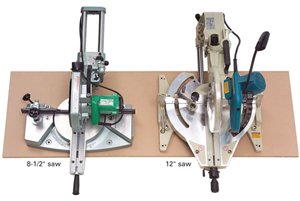

First and foremost, differences in size don’t necessarily mean big differences in capacity (see photos, right; Fig. B, below), or in the amount of space the saw takes up in your shop).

All the saws we looked at, even the diminutive 7-1/2-in. Makita, can easily crosscut dimensional 2×12 boards, even at a 45-degree bevel. Almost any board that can be cut on a 12-in. saw can be cut on a 10-in. saw. Most of those boards can also be cut on the smallest saw, but not always as easily. For instance, on a 10-in. or 12-in. saw, you can cut 1×4 baseboard standing up against the fence and it’s easy to shave a fraction of a degree off the cut to make it fit right. You can make the same cut on an 8-1/2-in. saw, but the baseboard has to be lying flat. This makes the cut slightly more difficult to set up and much more difficult to fine-tune, because the bevel scales are small and hard to read. On small saws, fractional bevel adjustments are hit or miss.

Crown molding can also be cut on any of the saws, but on small saws, the molding has to be cut flat using compound miter cuts—a skill that takes practice to master, especially with 7-1/2-in. and 8-1/2-in. saws that only bevel in one direction (see photo, above right). On 10-in. and 12-in. saws, standard crown molding can be cut leaning up against the fence, which makes cuts easier to visualize.

Performance and Features

The price difference between small and large saws (Fig. A, page 43) doesn’t translate into differences in performance. In side-by-side comparisons cutting the same hardwoods, we discovered little difference in the cutting speed and power of the different size saws. Surprising maybe, but it makes sense, because it doesn’t take as much power to drive a smaller-diameter blade. In our tests, the Makita 7-1/2-in. saw cut 1-3/4-in.-thick white oak faster, smoother and straighter than many of the 12-in. saws, and it was much less noisy, to boot. However, the smallest saws are not available with laser guides, and some have fewer accessories. Small blades cost less, but there are fewer to choose from. You’ll have numerous choices in 10-in. and 12-in blades. Usually, 12-in. blades cost the most.

Making the Decision

If you really need to cut big timbers, a 12-in. saw is the way to go. However, 10-in. saws have virtually the same crosscut and bevel capacity as 12-in. saws. They cut just as well, weigh less and cost less. And if you never cut anything thicker than 8/4 stock, the 7-1/2-in. and 8-1/2-in. saws deserve a close look.

My personal choice? My shop is in my basement, I’m remodeling my attic three floors up and my back is acting up. A 28-lb. saw that effortlessly slices 12-in.-wide boards of 8/4 hardwood sounds great to me. |

|

Thickness capacity is the major difference between small and large sliding saws. Every saw easily cuts through 8/4 stock, but only the 10-in. and 12-in. sliders allow cutting dimensional 4×4 timbers as well. It’s also easier to miter wide moldings and cut baseboards on the larger saws. Surprisingly, the differences in width capacity are marginal for the various saw sizes: Even the smallest slider cuts dimensional 2×12 boards.

Small sliding saws require just as much front-to-back space as large ones, because of the rails. All sliding saws require more space than the largest nonsliding miter saw.

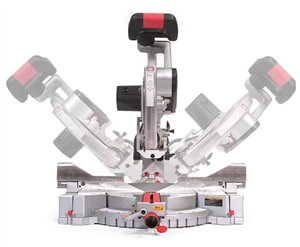

Virtually all 10-in. and 12-in. saws tilt both left and right. Bevel cuts can be more challenging on 7-1/2-in. and 8-1/2-in. saws, because they only tilt to the left.

|