Nothing signals skillful

craftsmanship like an

inset door with elegant

hinges and eye-pleasing margins. This

challenging job leaves no room for error:

Uneven surfaces and unsightly gaps will

tell the tale if the hinges, door and frame

don’t fit precisely. Like mastering handcut

dovetails, successfully hanging inset

doors on mortised butt hinges is a woodworking

milestone.

I’ll show you a three-step method for

installing inset doors that produces great

results every time. First, you match the

door to the opening. Then you rout

mortises for the hinges. And finally,

you create uniform, attractive margins

between the door and frame. Of course,

you can skip the mortising step altogether

by choosing different hinges (see

“No-Mortise Hinge Options,” below).

To complete the job, you’ll need a

couple simple jigs, a mortising bit, and

a laminate trimmer. A laminate trimmer

is a compact router that’s a really handy

addition to any woodworking shop. (If

you don’t own a laminate trimmer, this is

a great excuse to buy one.)

Round out your door-installing arsenal

with a pair of secret weapons—a plastic

laminate sample swiped from the home

center and a double-bearing flush-trim

router bit. This great new bit should be a

fixture in every woodworking shop.

Choose hinges

Your first task is to choose between extruded (also referred

to as drawn or cast) or stamped hinges (see photos).

Extruded hinges are machined and drilled, so there’s virtually

no play between the knuckles or around the hinge pin.

Stamped hinges are made from thinner stock. Their leaves are

bent to form the knuckles that surround the pin. Extruded

hinges will last longer, because their knuckles have more

bearing surface.

I often use stamped hinges because they cost about one third

as much as extruded hinges and they’re available at

most hardware stores. They work fine in most situations.

Examine stamped hinges carefully before buying. If you

notice large gaps between the knuckles and vertical play

between the two hinge leaves, keep looking. Be aware that

some stamped hinges are brass plated rather than solid

brass. Hinges with loose pins make it easy to remove and

reinstall the door, but they aren’t widely available.

Before you install the hinges, make sure the screws’

heads recess fully in the chamfered holes in the hinge

leaves. Amazingly, the brass screws supplied with brass hinges

often don’t fit. If that’s the case, you’ll have to deepen

the screw-hole chamfers or use smaller screws.

Brass screws are delicate. The heads strip easily or break

off, leaving the shaft buried in the wood. Avoid trouble

with broken brass screws by threading the pilot holes with

steel screws, which are much more durable. Install the brass

screws only once, after the piece is completely finished. Or

forget brass screws altogether and leave the steel screws in.

Friction-fit the door

I make each door about 1/32 in. larger than its opening.

Then I trim it to fit squarely and snugly. First I joint

the latch stile until the door slips between the face frame’s

stiles without binding. Then I check the door’s fit: While

holding the hinge stile flush against the face frame, I butt

the door’s top edge against the frame’s upper rail. If no

gap appears, the door and opening are square. Then I

joint the door’s top and bottom until the door wedges into

the opening—I want a friction fit, so the door stays put.

If the door or the face frame are out of square, I true

them by tapering the door’s hinge stile. I mark the end

that needs to be tapered while I hold the door in position

(Photo 1). If the gap along the top appears above the hinge stile, as in the photo, the side’s taper increases from

top to bottom. If the top’s gap appears above the latch

stile, the side’s taper runs in the opposite direction. The

taper increases from zero at one end to the width of the

top’s gap at the other end. If the top’s gap is wider than

1/16 in., I taper both the side and the end, removing one

half of the gap from each edge.

Routing is one way to taper the stile (Photo 2). You

could also use a hand plane or your jointer. Just make

sure the taper runs the full length and the tapered edge

is perpendicular to the door’s face. When both the hinge

stile and top edge fit properly without any gaps, trim the

bottom edge so the door fits snugly in the opening.

Rout the mortises

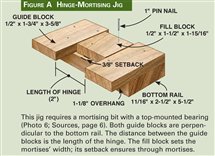

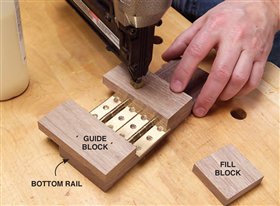

Make two jigs, one for routing the hinge mortises (Fig.

A, below; Photo 3) and the other to position the hinge in the

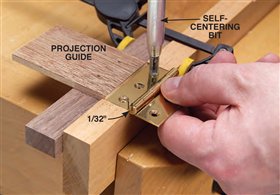

mortise (Fig. B, below; Photo 4). Then rout test mortises to

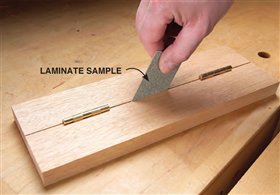

dial in the depth of cut (Fig. C, below; Photo 5). Laminate

samples make perfect gap testers for frame-and-panel

doors with stiles and rails up to 2 in. wide; these samples

are usually slightly less than 1/16 in. thick. Doors with

wider frame parts should have slightly wider gaps, because

they’ll exhibit greater seasonal movement.

Rout mortises in the door first (Photo 6). Make sure

they go in the correct stile! It’s easiest to rout hinge

mortises all the way through. If you want to rout halfblind

mortises, to shoulder the hinge leaves along their

length, simply modify your mortising jig by moving the

fill block forward to meet the hinge leaf. This modification

eliminates the need for the hinge projection guide,

but it requires squaring the mortise corners by hand

after routing.

No hard and fast rule exists for locating the hinges

on the door. One method is to align the hinge with

the door’s rails. However, this doesn’t work if the top

and bottom rails are distinctly different widths. Another

method is to divide the door’s length by six or seven and

center the hinges one unit from the ends. Use your eye

and trust your gut.

Carefully transfer the mortise locations to the face

frame (Photo 7). Your marks have to be perfectly located,

because the hinges fit the mortises so precisely. Use

the door’s top-to-bottom friction fit to hold it in position,

and make sure the door’s hinge stile is flush with

the face frame’s stile.

Rout mortises in the face frame (Photo 8). If you

don’t have a laminate trimmer, your options are to chop

these mortises by hand or to change your entire procedure

and rout these mortises first, before you assemble

the face frame.

Mount the hinges and create even margins

After mounting the hinges on the face frame, temporarily

install the door by pressing the mortises onto the mounted

hinges’ loose leaves. Then mark the door’s ends and latch stile

for trimming (Photo 9).

Remove the door, clamp on a straight board and rout the

ends to final length using a flush-trim bit with two bearings

(Photos 10 and 11). Clamp the board so its straight edge

barely covers the line; the line indicates the laminate sample’s

thickness and the goal is to remove exactly that thickness.

If you build during the summer’s high humidity when your

lumber is at its widest seasonal dimension, a one-laminate sample

gap between the door’s latch stile and the face frame is

sufficient. But if you build during the winter, it’s wise to provide

extra room for the door’s seasonal movement (Photo 12).

Fig. A: Hinge-Mortising Jig

Fig. B: Hinge Projection Guide

Fig. C: Mortise Depth

Sources

(Note: Product availability and costs are subject to change since original publication date.)

Woodcraft, woodcraft.com, 800-225-1153, Drawn brass cabinet

hinge, 2 in. x 1-1/2 in., #16R59; Stanley solid brass butt hinge, 2 in. x 1-3/8 in.,

#149747; Self-centering hinge-drilling bit, 5/64 in. for No. 3 and no. 4 screws,

#16i43.

Amana Tool, amanatool.com, 800-445-0077, Mortising bit, #45460-S.

Freud Tools, freudtools.com, 800-334-4107, Top- and bottom-bearing flush-trim

bit, 1/4-in. shank, #50-501.

This story originally appeared in American Woodworker May 2006, issue #121.

Purchase this back issue. |

|

Click any image to view a larger version.

1. True an out-of-square door by tapering the side, rather

than the end. The side is longer, so the taper will be

more gradual and less noticeable. In this case, making the

hinge stile narrower at the marked end will eliminate the gap

at the top.

2. Taper the side with a straight board and a flush-trim bit.

Position the board so it’s offset by the width of the gap

at the marked end and flush at the other end. Routing this

taper eliminates the guesswork associated with creating

tapers with a jointer.

3. Use the hinges to make your mortising jig. This guarantees

that the hinges will perfectly fit the mortises. After

installing the guide blocks, add the fill block to provide continuous

support for the router.

4. Locate the hinges on a test piece, using a projection

guide to position the center of the barrel 1/32 in. out from

the board’s face. Drill pilot holes using a self-centering bit.

5. Test the mortise depth by mounting hinges on scrap

stock. The gap should equal the thickness of laminate. If

the gap is too wide, the mortises aren’t deep enough. Widen

a gap that’s narrow by jointing the door stile.

6. Rout mortises in the door stile. Locate the mortise at

least one hinge length from the top. Because of its small

size, a laminate trimmer works great for this delicate job.

7. Transfer the mortise locations from the door to the face

frame using a straightedge. The door’s snug top-to-bottom

fit holds it in position.

8. Rout mortises in the face-frame stiles using the mortising

jig. You’ll need a laminate trimmer for this job,

because the mortises are so close to the corner.

9. Mark the door’s final size, using a laminate sample to

establish uniform gaps. Slightly recess the door in the

opening, using the hinges and the top-to-bottom friction fit to

hold it in position. Mark with a mechanical pencil, so there’s

no gap between the laminate and the line.

10. Rout the door to final length. Use a fence and a flushtrim

bit with top- and bottom-mounted bearings to

avoid blowing out the back edge. First, rout halfway using

the top bearing.

11. Flip the door over, adjust the bit to use the bottom

bearing and finish routing.

12. Allow for seasonal movement between the door’s latch

stile and the frame. Make the gap wider if you build

during the winter, when the humidity in your heated shop is

probably significantly lower than during the summer months.

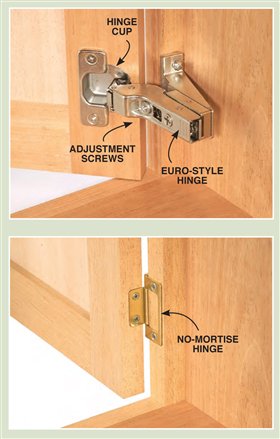

No-mortise hinge options

If mortising hinges isn’t your idea of woodworking

fun, consider one of these two options for

mounting inset doors.

Euro-style hinges only require drilling holes for

hinge cups and mounting screws. They also have

the advantage of adjustability: Once the door is

installed, you can easily move it up or down, side

to side and in or out—whatever it takes to even up

the margins. These hinges take up a lot of space

inside the cabinet, though, and some versions only

swing open to 95 degrees.

No-mortise hinges are quite simple to install

and they leave an acceptably narrow gap. Some

no-mortise hinges have elongated slots for adjustability.

Still, the door must be carefully fitted to the

opening and the hinge locations have to be carefully

laid out. It’s a good idea to use a projection guide,

like the one shown in Photo 4, to ensure that the

door and frame faces will be flush. No-mortise

hinges are available in a variety of finishes, including

polished and satin brass, but they’re often

made of plated steel instead of solid brass. |