We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

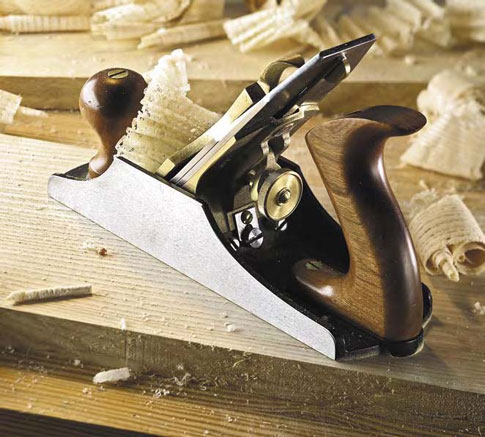

The bench plane has three jobs in the woodshop: to straighten the wood, to smooth it and to remove it.

It sounds so simple when you put it that way, but many woodworkers are confused by all the different sizes of bench planes available, from the tiny 5-1/2″-long No. 1 smooth plane up to the monstrous 24″-long No. 8 jointer plane.

Add into the mix all the new bevel-up bench planes that are available in the catalogs now, and it’s bewildering enough to make you want to cuddle up close to your belt sander.

Believe it or not, there is a way to make sense of all the different sizes and configurations of bench planes out there and to select the few that you need in your shop. You don’t need one bench plane of each size to do good work (though don’t tell my wife that). In fact, it’s quite possible to do all the typical bench plane chores with just one tool (more on that later).

In this article, I’m going to walk through the entire line of forms of the metallic-bodied bench planes and describe what each tool is good for. Because people can work wood in so many weird ways, I’ll admit that what follows is equal doses of traditional workshop practice, personal preferences (formed by years of planing) and stubborn opinion that comes from growing up on a mountain.

But before we jump headfirst into describing each plane, let’s first divide the tools into three broad categories: smoothing planes, fore planes and jointer planes.

Three Jobs for Three Planes

You can tell a lot about what a plane is supposed to do by the length of its sole.

• Smoothing planes have a sole that ranges from 5″ to 10″ long. The primary job of the smoothing plane is to prepare the wood for finishing. It is typically the last plane to touch the wood.

• Fore planes have a sole that ranges from 14″ to 20″ long. The traditional (but by no means only) job of the fore plane is to remove material quickly. By virtue of its longish sole it also tends to straighten the wood to some degree. The fore plane is typically the first bench plane to touch the wood to get it to rough size.

• Jointer planes have a sole that ranges from 22″ up to 30″ (in wooden-bodied planes). The primary job of jointer planes is to straighten the wood, a task it excels at by virtue of its long sole (the longer the sole, the straighter the resulting work). The jointer plane is used after the fore plane but before the smoothing plane.

Smoothing Planes

Let’s begin at the small end of the scale and look at the smoothing planes. People tend to end up with several of these (sometimes even in the same sizes). Why? Well there’s a lot to choose from and different ways to configure them.

A collector’s dream: An entire tray of No. 1 planes.

The No. 1 Bench Plane

Sole length: 5-1/2″

Cutter width: 1-1/4″

Prized by collectors, the No. 1 bench plane is like an exotic little dog. It is designed to make people pick it up and say, “It’s so cute!” And it’s designed to empty your wallet – it’s easy to spend $1,000 on a vintage No. 1 plane. With a price like that, it’s got to be one amazing and useful plane, right? Nope.

Some woodworkers like to use the No. 1 in place of a block plane – woodworkers with arthritis report that it’s easier to cradle in their hands than a block plane. Some woodworkers buy a No. 1 for their children. Some woodworkers have special small-scale applications for the No. 1, such as working linenfold panels.

But in reality the No. 1 is not a useful size for building most furniture. You can’t hold it like a regular bench plane because there’s not enough space in front of the tote. And adjusting the depth of cut is no fun either because of the cramped area behind the frog. Add to that fact that the cutter is so narrow and you can see why you’d be working way too hard to plane a typical carcase side.

Buy one because you want one. But don’t fool yourself into thinking that you’re going to use it all that much. Most woodworkers end up putting it on a shelf and admiring it.

The No. 2 Bench Plane

Sole length: 7″

Cutter width: 1-5/8″

Pity the poor No. 2 bench plane. It’s not as rare as its smaller and cuter sibling, nor is it all that much more useful. Collectors love them, though the No. 2 doesn’t fetch the same prices as the No. 1. Woodworkers are bewildered by them. It’s almost impossible to grip the tote because things are so cramped in there. And holding the tool makes you feel like you’re an awkward giant.

I do hear occasionally that the No. 2 is a good smoothing plane for children. It’s usually big enough for their hands, and it isn’t terribly heavy. The vintage ones were 2-1/4 lbs. And I’ve heard from maybe one woodworker in all my years that they had abnormally small hands that were suited for a No. 2. But other than that, I think it’s best to avoid the No. 2 bench plane unless you stumble on some unique application.

A No. 3 smoothing plane.

The No. 3 Bench Plane

Sole length: 8″

Cutter width: 1-3/4″

The No. 3 is one of the most overlooked planes in the pantheon. Because of its small size, it gets lumped in with the No. 1 and No. 2 in the category of “cute but useless.” Nothing could be further from the truth. If I were manufacturing a line of handplanes, the No. 3 would be the smallest plane I’d offer in my line. It truly is a useful tool.

You can actually get your hand comfortably around the tote and work the controls with great ease. The front knob is big enough to grasp like a traditional bench plane. And the cutter is just wide enough to be a useful size. So what is it good for? I use a No. 3 for two things: smoothing small-scale parts (such as narrow rails, stiles, muntins and mullions) and for removing tear-out in very localized areas in a larger panel.

The tool is ideal for small parts because you can easily balance it on stock that is only 3/4″ wide without tipping or leaning problems.

As for removing tear-out, it’s the sole’s small length that makes this possible. The shorter the sole, the more that the tool is able to get into localized areas on a board and remove tear-out. The long sole of a No. 4 or larger plane will actually prevent the tool from removing more than a shaving (maybe two) in a small area. The No. 3 goes where my other tools simply won’t.

The No. 4 Bench Plane

Sole length: 9″

Cutter width: 2″

The No. 4 smoothing plane is historically the most common size. It is an excellent balance of sole length and cutter width to be useful for typical furniture parts. And the last part of that sentence is what is important here: typical furniture parts. Typical furniture parts range from 2″ wide to 24″ wide and 12″ long to 48″ long. That’s a gross generalization, but it works.

Here’s another clue that the No. 4 is useful and popular: When you are searching out a vintage one, you’ll find 10 No. 4s for every one No. 3.

I use a No. 4 for most of my typical cabinet work. And because I work with hardwoods, I have equipped my No. 4 with a 50° frog, which helps reduce tearing (a 55° frog also is available for reducing tearing in curly woods). This is not the tool I’ll use for really tricky domestic woods or exotics – I use a bevel-up plane for that (see below).

Another important detail of the No. 4: It’s not terribly heavy and won’t wear you out as quickly as the bigger smoothing planes.

A Lie-Nielsen 4-1/2 smoothing plane.

The No. 4-1/2 Bench Plane

Sole length: 10″

Cutter width: 2-3/8″

What a difference an inch makes. The No. 4-1/2 is a little bigger than the No. 4, but that additional metal is a game-changer. The No. 4-1/2 smoothing plane is more popular now than it was when Stanley was the only game in town. Why is that? Good press. Lots of high-profile woodworkers have sung the praises of this size tool. And, as Americans, we also seem to like things that have been Super-Sized.

In truth, the No. 4-1/2 is an excellent size tool, though it’s more apt to wear me out faster because it’s heavier and has a wider cutter. So it requires more effort to push the tool forward.

Of course, the advantage of the wider cutter is that you’ll get the work done in fewer strokes, so that might be a wash. And the advantage of the extra weight is that the tool will stay in the cut with less downward pressure on your part. So it’s not the simplest of trade-offs to calculate.

I think the No. 4-1/2 is ideal for woodworkers who like a big and heavy plane (a legitimate preference) and those woodworkers who work on larger-scale furniture. If you build jewelry boxes, the No. 4-1/2 likely isn’t for you. If you build armoires, you’ll love it.

The No. 5-1/2 Bench Plane

Sole length: 15″

Cutter width: 2-1/4″ or 2-3/8″

No, this isn’t an error. I meant to put the No. 5-1/2 in the smoothing plane section. Despite the fact that the No. 5-1/2 is 6″ longer than a typical smoothing plane, I think a legitimate case can be made today that it serves as a smoothing plane more often than not.

Why is this? English craftsman David Charlesworth. Charlesworth has been a passionate advocate of setting up this sized tool as a so-called “super smoother” that is used in a modern shop to both smooth and straighten the wood. The No. 5-1/2 is midway between a jointer plane and a smoothing plane, which is why this arrangement works.

In a nutshell, the No. 5-1/2 is the same size as a historic English panel plane, a form of tool that was uncommon in the United States. English craftsmen would use a panel plane for smoothing large surfaces.

The modern No. 5-1/2 is a perfect companion to the woodworker with a powered jointer and planer and who doesn’t want to set up a bunch of planes. Here’s the drill: You dress all your lumber with your machines and then use your No. 5-1/2 to refine the stock; the No. 5-1/2 trues up the work more than the machines can and it smoothes the work simultaneously.

There are disadvantages to any “one plane” approach. The middling size of the sole makes it difficult for you to get into localized areas to remove tear-out (shorter tools do this with ease). Plus, the tool is difficult to use to shoot long edges for a panel glue-up – a real jointer plane makes this task simpler.

However, the No. 5-1/2 does handle more than 90 percent of your work-a-day chores if you own machines. I’ve worked the Charlesworth way on several projects and have found his methods to be correct and reliable.

A Veritas bevel-up smoothing plane.

Bevel-up Smoothing Planes

Sole length: 9-1/2″ to 10″

Cutter width: 2″ to 2-1/4″

The modern bevel-up smoothing planes have become quite popular recently. They are simpler tools (with no chipbreaker or movable frog), they’re less expensive than their bevel-down counterparts, and they are easily configured to plane at high angles that reduce tear-out.

With all those advantages, why did I even write about all the bevel-down smoothing planes. It seems a no-brainer.

Well, it’s not that simple. With the bevel-up tools you have to give up a few things. These are important to some woodworkers (myself included) and insignificant to others. You have to be the judge here.

First, there’s the position of the controls. Traditional bevel-down planes have the blade adjuster right where you want it: in front of your fingers. You don’t even have to remove your hand from the tote to adjust the depth. In fact, you can adjust the cutter while the plane is moving. I do this all the time.

With bevel-up planes, the controls are low on the tool – too low to reach without removing your hand from the tote.

Second trade-off: lateral-adjustment controls. With traditional bevel-down planes there are separate controls for depth adjustment and lateral adjustment (which centers the cutter in the mouth of the tool). With Veritas’s bevel-down planes, both controls are integrated into one adjuster, called a Norris-style adjuster. Some people love this arrangement. Some struggle with it and find that they cannot separately control the two functions (depth and lateral adjustment). The Lie-Nielsen bevel-up plane, the No. 164, is adjusted laterally with hammer taps, so it has a different feature set.

Third trade-off: comfort. If you like a traditional bevel-down plane, working with the bevel-up planes can be disconcerting. There’s no place to rest your index finger except on the tote itself. And if you were trained to extend your index finger, you feel naked, weird and alone (or maybe that’s just me).

All that said, the bevel-up planes are extraordinary tools for eliminating tear-out. Because the bevel faces up, you only have to hone the cutter to a higher angle to raise the cutting pitch of the plane. This is a tremendous game-changing advantage and is the reason that I really like the bevel-up tools and keep one handy that’s set with a high cutting angle (I like 62°).

If you work with exotics or curly woods, I wouldn’t even bother with the traditional bevel-down tools. Sorry, but that’s how I feel. I’d go straight to the bevel-up models. You’ll be happy.

But if you work with mild domestics, you should consider the trade-offs between the two forms before you make a purchase. In fact, the two formats are so different in the hand that I think it’s worthwhile to take a test drive of each form to see which you like better.

The Fore and Jack Planes

Welcome to the weird middle ground of plane sizes, where any tool can do any job and trade-offs abound. Historically, this size plane was used for roughing. You’d put a heavily cambered iron in the tool, open up the mouth all the way and take off huge ribbons of wood. In this day and age of inexpensive and accurate machinery, few people use this size tool in this historical manner. Let’s take a look.

A Stanley No. 5 jack plane.

The No. 5 Bench Plane

Sole length: 14″

Cutter width: 2″

Commonly called a jack plane, the No. 5 is the most common plane out there. If a pre-war homeowner bought one plane, it was most likely a jack plane. Why? Well the jack plane can be set up to do almost any job.

Camber the iron and it can be a fore plane for removing stock. Set it up with a straight iron or a slightly cambered iron and it can be a shortish jointer plane. It won’t work as well as a jointer plane for this, but you can get away with a lot, actually. Set it up with a minutely cambered iron and take a light shaving and you can use the jack as a long-ish smoothing plane. Once again, it won’t be the end-all smoothing plane, but you’ll be surprised what you can do.

I know all this because this is how I worked when I had only one bench plane, a vintage No. 5. When people ask me what plane to buy if they only bought one, I usually recommend a No. 5 or its bevel-up equivalent.

Now that I own many more planes, I use the No. 5 as a fore plane. With a heavily cambered iron, I use it to dress stock that is too wide for my jointer or planer. With a sharp iron and mild material I can remove almost 1/16″ off at a time. It’s a powerful, effective and useful tool, even in a shop filled with machines.

The No. 5-1/4 Bench Plane

Sole length: 11-1/2″

Cutter width: 1-3/4″

Sometimes called the junior jack plane, tool collectors tell me that this plane shows up in a lot of inventories of manual training programs at public schools. It was a little lighter and shorter than the traditional jack, which made it easier for the shop-class misfits to wield.

I have only limited experience with this tool and have never owned one. My short stint with the tool was enough to convince me that there’s a reason that it’s an uncommon size. It was really too short to joint an edge accurately. The cutter width was the same as a No. 3, but the longer sole prevented it from getting into hollows like a smoothing plane.

If you’re a devotee of this tool, I want to hear from you.

A Stanley No. 6 fore plane with a scraping insert installed.

No. 6 Bench Plane

Sole length: 18″

Cutter width: 2-3/8″

The No. 6 bench plane, which Stanley actually called a fore plane, gets a bad rap. Patrick Leach, who administers the excellent Blood & Gore plane-reference site, runs down the No. 6 as a fairly useless chunk of iron. Here’s how he puts it: “You Satan worshipers out there might find them a useful prop during your goat slicing schtick by placing three of them alongside each other.”

I’ve owned a few No 6s and actually like them. I’ve set them up as fore planes, and they work quite well at that task. I’ve set them up as jointer planes, and they work surprisingly well at that task. In fact, I’ve found that it’s easier to teach someone to joint an edge with a No. 6 than one of the longer planes. There’s just less iron swinging around I guess.

I also have one set up with a scraping insert. Did I hear you say that’s nuts? Well, I thought so too, but it’s a great set-up for glued-up tabletops. Here’s why: When you glue up a tabletop from narrower boards, it’s tough to get the grain in all the individual boards going the same direction and looking good.

So when you go to plane down the tabletop, you run into lots of grain reversals. One way around this problem is to change planing directions several times while working the top. That can be tough sometimes. Or you can scrape the top – and that’s one of the best tasks for a scraper plane. And with a scraper plane that is long (like my No. 6) I can scrape the entire top without leaving any dished areas, which is more a problem with cabinet scrapers, card scrapers and short scraper planes.

The good news is that No. 6 planes are fairly plentiful on the secondary market and reasonably priced. Thanks Patrick!

A Veritas bevel-up jack plane on a shooting board.

Bevel-up Jack Planes

Sole length: 14″ to 15″

Cutter width: 2″ to 2-1/4″

One of the most common questions I get here at the magazine goes something like this: “I’m a beginner. I want to buy one premium handplane, and I want it to do the most tasks possible because I cannot afford a whole set of tools. Which tool should I buy?”

The answer is to buy one of the bevel-up jack planes. Yes, there are trade-offs (see the section above on the bevel-up smoothing planes), but these bevel-up tools are extraordinarily useful, versatile, adaptable and easy to use.

If you buy a couple extra irons, you can have a longish smoothing plane with a high cutting angle. You can have a shortish jointer plane that is good for jointing edges up to 36″ long. And you can put a straight iron in the tool and use it for shooting the ends of boards. No other plane that I own can do all three things like the bevel-up jack planes.

The one thing the tool doesn’t do very well is to work as a fore plane. I haven’t had much luck putting a heavily cambered iron in the tool and taking a super-thick shaving. Perhaps there’s some geometry at work there. Maybe I’m doing something wrong.

Jointer Planes

The longest tools in the bench plane family are designed to straighten and flatten the work. They are one of the most important tools in my kit, though many woodworkers go their entire careers without picking one up.

A Lie-Nielsen No. 7 jointer plane.

No. 7 Bench Plane

Sole length: 22″

Cutter width: 2-3/8″

Some woodworkers use a No. 7 plane for all their planing needs. Woodworking legend Alan Peters is said to use a No. 7 for jointing, smoothing and shooting. And if you set the tool up precisely and are a careful craftsman, you’ll find this is quite do-able. Like my experiments with a No. 5-1/2, I tried using a No. 7 for everything as well. I was surprised how easy it was, once I got used to the weight of the tool and balancing it on small pieces of work.

In a traditional shop, the No. 7 is the most common size of jointer plane. It is used for shooting the long edges of boards to form them into a wider panel. And it is used for dressing the faces of boards to make accurate surfaces for joinery.

Here’s how I use a jointer plane in my shop. I dress my stock using the machines, and then I further refine the faces and edges with a jointer plane. Sound fussy? Try it some time. Most machinery can get your boards only so flat. A jointer plane can take them one step further. And accurately prepped stock can help you when it’s time to cut your joints.

I also use it to joint the edges of boards for glue-ups. The jointer plane allows me to add a spring joint to a panel glue-up. A spring joint is where you plane the middle section of the edge a wee bit hollow. When you close up the joint with a clamp at the center, it closes the ends tightly. This allows you to use fewer clamps and keeps the ends of the joint in tension. This can be helpful with some stock because the ends of your panel will lose and gain moisture more rapidly than the center. So the extra pressure keeps everything together when the dry season hits.

There’s a lot of controversy about how the jointer plane’s iron should be sharpened. Some like it straight. Some like it curved. I use a slightly curved iron because it makes it child’s play to correct an out-of-square edge. And when I plane the faces of boards, the curved iron reduces the chance that the corners of the iron will dig into the work.

A No. 8 Lie-Nielsen jointer plane.

No. 8 Jointer Plane

Sole length: 24″

Cutter width: 2-5/8″

The No. 8 seems only a little bigger than the No. 7. But in reality, the No. 8 is a big beast of a tool compared to the No. 7. There seem to be some tipping points when it comes to the sizes of planes, and the No. 8 definitely tips the scales into a whole different class of tool.

Some people really dislike the extra weight and width of the tool. Other woodworkers love it. I fall into the “love it” category. Though I use a No. 7 at work, I keep a No. 8 in my shop at home (perhaps so I don’t have to share).

I’ve found that the No. 8 works like a freight train. Once you get it started, there’s little that will stop it. This is useful when dealing with patches of tough grain. The No. 8 just snowplows through.

The extra weight does come at a price: Surfacing boards can be more tiring. And you have to keep the iron sharper than you do on the No. 7. All the extra mass and width makes the No. 8 harder to push around when the iron gets a little dull. Oh, and you’ll want to keep some paraffin on hand to wax the sole. That’s a good idea for any plane, but it’s particularly true for the big boy of the planing world.

Bevel-up Jointer Planes

Sole length: 22″

Cutter width: 2-1/4″

Because of my affection for the bevel-up jack plane, you’d think I’d have the same enthusiasm for the bevel-up jointer. Not so much.

The bevel-up jointer plane is easier to use than its bevel-down cousin. And it is less expensive. But it also has a lower center of gravity, and I think that’s why I’m not as fond of it. The high center of gravity of the bevel-down jointer plane makes it easier for me to sense when the tool is tipping to the left or right. In other words, I can feel “plumb” better with a bevel-down jointer plane. The bevel-up jointer plane doesn’t give me that same feedback.

Other than that detail, the trade-offs are the same when you consider a bevel-up vs. a bevel-down tool.

Christopher Schwarz is editor of Lost Art Press and a contributing editor to Popular Woodworking Magazine. For more on all things handplanes from Chris, get his book “Handplane Essentials” – now in paperback.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Chris, I thought that maybe since you mentioned a 30” wooden bodied jointer, that you were going to elaborate on one, but alas nothing was said, so I did build a 30” long 18th century jointer plane from the instructions from the DVD that Bill Anderson made. It is my go to plane when jointing a long edge. It is not monstrously heavy, but it will tame the tool marks from a big box store piece of lumber in a heart beat. It can be set-up to take anything from a thick shaving to a wispy gossamer shaving. I would encourage anyone with an inkling to make your own handplane to give this one a try.

I would like to try setting a 5 1/4 up as a scrub. Has anyone tried that?

Keep trying to find one for a bargain that is in rough enough shape I would mind modding it. I would think the narrow width would lend it to work well there.

I haven’t converted a 5-1/4 to a scrub plane, but as an alternative, I did make a 78 into a scrub plane. I followed Paul Sellers advice and it took about 15 minutes to reprofile and sharpen a 78 iron into a scrub plane. It does work beautifully. Paul Sellers also show how to convert a #4 into a scrub plane, so a 5-1/4 would be just fine.

Great article, I’ll definitely refer to this many times. In the section on the number 7, where you say tension, I think you mean compression.

Christoper Swartz does it again, with another great article. This article should be a pre requisite to buying a plane. Always keep in mind though, No matter what plane you have, learning to set up the blades and sharpen them is the most crucial part of it all. Most people get frustrated when their plane don’t perform properly. This is usually caused by not properly setting up the planes. Buy a decent older Stanley plane and learn how to fix it up and tune it. Don’t go out and buy the most expensive one and think its going to make you a woodworker. Learn the techniques and stay with it.

I wish I saw and red this article when it came out, I could have save myself a bundle and buy the “real” necessary hand planes and maybe that way I could have bought myself some LN planes instead of a lot of “other” planes. I own some “cheap” imitations of LN like WoodRiver #4,5 and 6 which are not bad tools all together and a LA Veritas Jack plane, which I consider my Cadillac of planes. I got a 38 degree blade extra for hard woods and the finished wood from shavings of this plane are smooth as glass. Now that I learned how to sharpen these blades, “all” my planes whisper when they shave wood. Here is something interesting: last year I bought a book Working Wood 1 & 2: the Artisan Course with Paul Sellers and read it, also he has a lot of interesting videos on You Tube which are by all means, phenomenal, in his opinion, he’s using only “ONE” plane a #4 Stanley vintage, I saw him this year at a woodworkers show in NJ, with “ONE” plane (he has a lot of them, but swears by that #4).

I don’t want to take away Chris’s thunder from this article which I found most interesting, thanks.

Nicely done.

This is a terrific guide for anyone wanting to get an idea of what they need and why (or why not), especially for anyone starting out. I had read a multitude of articles before I got started with handplanes and if I had had seen this one first, all the others would have made a lot more sense.

I also learned that my #6 isn’t as mysterious as I thought it was (and now, to find a scraper insert for it!). I too, use it for jointing.

Again, nicely done.

Wonderful article on Bench Planes. However I find I reach for my Block Planes much oftener Easing edges, bevel, radius. I would to see an article on them.

Given that this was posted over four years ago, I’m really surprised that no comments have been posted yet.

This is a very helpful blog with lots of good well-thought-out information.

Nicely done.

Christopher, no, I don’t have a #6, and probably will not buy one.

The only plane I’ve had is a Record 5-1/2 purchased new many years ago. It has met all of my needs so far. Getting back into wood working, I’ve ordered a LN 102 and am shopping ebay for a #4 and #7, probably Stanley, given the number of them on the market.

thanks for the blogs.